The Risk that Glows in the Dark

It is fairly likely that by 2030 a nuclear attack will have hit one or more major Western cities.

April 18, 2015

The proposed U.S.-Iran treaty is a useful reminder of various nations’ nuclear ambitions. Whatever the ultimate outcome of this particular effort, here is an uncomfortable forecast to ponder carefully.

It is fairly likely – perhaps a 25% probability — that by 2030 a nuclear attack on one or more major Western cities will have taken place.

The attacker will probably be either an independent terrorist group or an anti-Western minority element of the military in a country with nuclear weapons and imperfect control of its armed forces. Such an outcome is increasingly more likely in a future where more nations become nuclear powers.

Fallout

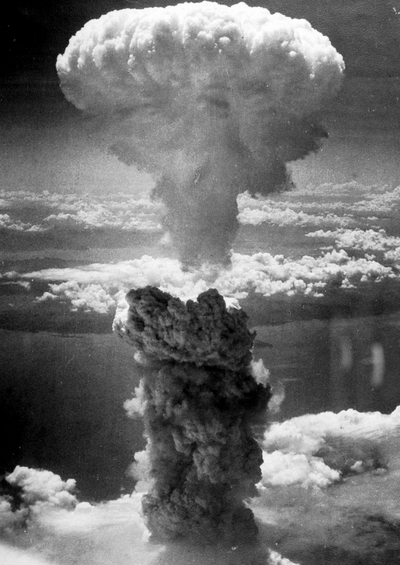

The casualty level for such an attack will be in the hundreds of thousands in the short term, and the low millions in the long term. Higher casualty levels in the tens of millions are unlikely, assuming the attacker has not developed the more complex and sophisticated thermonuclear weapon capability.

It is also possible that one or more uses of nuclear weapons will have taken place in the Middle East or around the Muslim/Christian divide in Africa.

The “foreign policy” question of how the West should respond to such an attack will depend on its details, and is in any case well above my “pay grade.” I will focus on the equally important question of what effect such a “successful” attack will have on the global economy.

It is overwhelmingly likely that the first successful nuclear attack, or possibly the first outside the Middle East/North Africa, will be made against one of about half a dozen major global cities.

As such, its victims are likely to include a sizable number of well-known people, as well as a disproportionately high number of victims in the financial services industry, media and politics.

The precise outcome will depend on which city is targeted, as will the predominant nationality of the victims. A Paris attack would produce different victims of an attack on New York, for example, while an attack on Los Angeles would be different again.

Post-attack changes

Absent a major war, only a few cities are overwhelmingly likely to be targeted by such an attack. The main economic response in view of such a risk would be to opt for more decentralization post-haste.

Overwhelming concentrations of financial, media and political power render a city especially vulnerable to nuclear attack, while smaller concentrations in regional cities are much less likely to attract the attention of potential bombers.

Given the capabilities of modern communications, in any case, the need for physical concentration in an activity is much less than it was 30 years ago.

Thus, the rational response at this stage ought to be that vulnerable institutions would decentralize – by moving to provincial cities.

In Britain, the overwhelming dominance of London would be ended, with the Bank of England perhaps moving to Manchester, while the London Stock Exchange, really at this stage a bunch of servers and some senior management, could be relocated, say, to Birmingham.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City might become the central nexus of the overall Fed system.

Economically, such a response would be very healthy indeed, except for the cities that risk suffering, or by that time, may have suffered an attack.

Affordable real estate

The concentration of wealth in the half-dozen “world cities” has inflated their real estate costs beyond belief, and made them almost uninhabitable for all but the very (global) rich, and impossible for the young to settle down in unless they inherit a house.

For now, the property markets in such places are serious promoters of excessive inequality and represent serious blocks against social and career mobility. Decentralizing the countries in question beyond their “trophy” cities would be a major boon.

The long-term prognostications are gloomier. Unless some mechanism is found whereby nuclear proliferation can be reversed, nuclear weapons will proliferate further.

Eventually, some group will acquire one that merely wants to spread terror, without any notable political goal, in which case the restricted list of vulnerable cities will expand to include anywhere with a substantial population.

Thus, when investors are assessing global risks from here on out, nuclear proliferation is certainly one risk they should take very seriously.

Editor’s Note: This article is adapted from an article originally published on the True Blue Will Never Stain.

Takeaways

It is fairly likely that by 2030 a nuclear attack will have hit one or more major Western cities.

The next nuclear attack will be by a non-state actor: terrorists or a rogue-element of a nuclear capable military.

Economic decentralization is the only way for a Western nation to survive a nuclear attack on its capital.

Unless a mechanism is found to reverse nuclear proliferation, nuclear weapons will proliferate further.