China: Rethinking the Yuan Devaluation

Understanding China’s currency move from a non-Western-centric perspective.

August 13, 2015

A few days ago, on August 11, 2015, the People’s Bank of China lowered the yuan’s exchange rate by almost 2%. The central bank’s move pushed the yuan’s “daily fix” to 6.2298 against the U.S. dollar.

This move was its biggest one-day change since China had loosened (somewhat) its dollar peg back in June 2010. Financial market observers immediately jumped to two “conclusions:”

- First, while China’s central bank in its announcement of the move paid lip service to a more flexible exchange rate regime, its action really signaled panic about China’s slowing growth.

- Second, this devaluation wasn’t a one-time shot, but rather the likely start to a prolonged period of engineering the yuan downwards in a resolute effort to increase China’s external competitiveness.

As news of the devaluation spread, all China-sensitive asset prices — such as oil, copper, shares of luxury brands and cars, and emerging-market currencies — dove below their already-depressed price levels

A non-Western view

While the markets’ reaction reflected a lot of “first world” frustration, look at this latest development in China from a non-Western-centric perspective. Viewed from this angle, the market reaction and commentary we have seen to date is myopic.

Even if the devaluation signals concerns about China’s current growth path, correcting the yuan’s accumulated overvaluation will be good for China’s (and other emerging countries’) growth as well as commodity and luxury exports.

This may sound like a bewildering thought in the context of the still-dominant Western opinion. But in the new world we live in, two facts of life stand out: First, how China’s economy fares — and, by extension, the other emerging markets, accounts for a far more significant share of humankind than the effects on Western countries. (China’s population of 1.3 billion is roughly equal to the combined population of the wealthy OECD nations.)

Second, the latter markets — and especially the U.S. ones — are already way too “mood-dependent” on what happens in China. Particularly worrisome is the rather passive mindset, especially pronounced in the United States — to hope that “China will be fine, so that we don’t have anything to worry about.”

A fair foreign exchange rate

Some may still doubt that the yuan is overvalued. But let’s look at the evidence. According to the broad measure of the Bank for International Settlements’ effective (i.e., trade-weighted) exchange rate, the Chinese yuan has appreciated by some 30% over the past five years.

And according to Barclays’ behavioral equilibrium exchange rate model, the yuan remains the second-most overvalued currency in the world, by more than 20%.

Enlarge Yuan BIS Effective Exchange Rate, 01/2010 — 06/2015

Enlarge Yuan BIS Effective Exchange Rate, 01/2010 — 06/2015The U.S. dollar’s recent ascent has pulled the yuan away from other currencies, leaving it increasingly overvalued, as the yuan has stayed on a soft peg to the dollar.

Even the Peterson Institute, traditionally regarded as the U.S. Treasury’s ventriloquist and thus prone to accuse China of unfair exchange-rate protection, has recently calmed down. It now gauges China’s so-called fundamental equilibrium exchange rate as “correctly” valued, at around 6 yuan per dollar.

A further indication of yuan overvaluation — not undervaluation, as is widely charged in the confines of the U.S. Congress — is that markets as well as Chinese corporations had been expecting a yuan depreciation going forward.

Evidence of this is the surge of onshore foreign exchange deposits in China in 2014, largely due to corporations holding more of their export proceeds in foreign currencies.

Growth linkages: China and the world?

What about the critical linkage from China’s economic fortunes to those of the other emerging markets?

It is largely ignored that China is the world’s most efficient country to turn currency depreciation into higher growth — and, by extension, world growth — as its growth has increasingly mattered for poor and rich countries alike.

According to estimates by Harvard economist Dani Rodrik, a 10% nominal effective appreciation of the yuan would lower China’s annual growth by 0.86 percentage points. Thus, the 30% appreciation which occurred over the past five years may have trimmed 2.5 percentage points off China’s growth rate.

This reduction in China’s growth has translated into a drop of GDP growth in poor countries. Research at the OECD about growth linkages between China and poor countries has produced growth sensitivity estimates of 0.34%.

Consequently, a drop of 2.5 percentage points in China’s growth rate has taken one percentage point of annual growth in developing countries.

The growth link between China and the emerging markets was even higher, with one percentage point of growth in China translating into 0.66 percentage points of growth in the emerging markets.

These macroeconomic mechanics of growth can constitute a certain degree of optimism for future economic growth in China and emerging countries as well as for commodity prices and world trade — provided that the People’s Bank of China follows up its 2% devaluation in August with further devaluations.

Takeaways

Correcting the yuan’s accumulated overvaluation is ultimately good for China’s commodity and luxury imports.

The yuan remains the second-most overvalued currency in the world, by more than 20%.

Peterson Institute said China's so-called fundamental equilibrium exchange was "correctly" valued.

The 30% appreciation of the yuan in the past 5 years may have trimmed 2.5 points off China’s growth rate.

Read previous

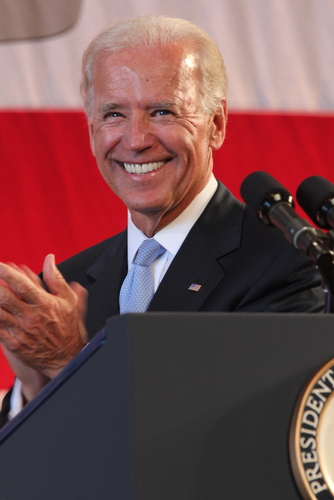

Joe Biden: Just Bidin’ His Time

August 13, 2015