Are Most Women Predisposed to Lead More Ethically?

Exploring the links between gender, morality and power.

August 25, 2024

A Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.

Women have become increasingly visible in leadership positions in business, academia, civil society and politics, as demonstrated by the rising number of countries with female heads of government.

An issue debated since Indira Gandhi’s time

The perceived strengths and weaknesses of top-level women decision-makers have long sparked debates about their rise and eventual fall. Just consider the cases of Indira Gandhi in India, Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Angela Merkel in Germany, among others.

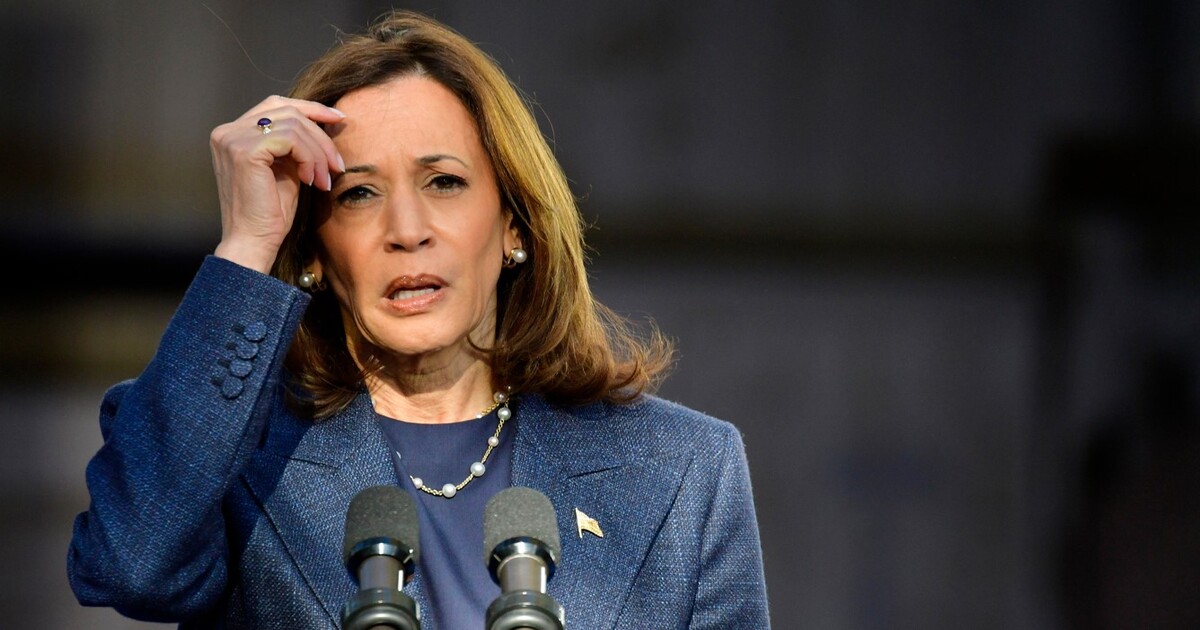

The current U.S. presidential campaign, which is pitting a woman against a man, has also brought the issue into sharp focus.

Politically tinged estrogen versus testosterone wars

Yet, male dominance in global leadership roles persists, despite ample evidence demonstrating the benefits of female leadership.

This has revived the politically tinged estrogen versus testosterone wars. Commentators of all stripes squabble over who makes better leaders, men or women.

Better look at neurobiology and neuropsychology

To make meaningful progress in this debate, we would be well served to also look further afield, to neurobiology and neuropsychology. This will help us understand the foundations of responsible leadership and the relationship between gender, power and morality.

Recent research suggests that women could be more relational and less likely to undertake moral transgressions. Behavioral studies and neuroimaging research have revealed that males and females vary in their moral judgments and in behaviors related to morality, such as empathy and aggression.

Are women managing power more ethically and efficiently?

This raises a set of timely questions related to responsible decision-making: Are the strengths that women bring to leadership linked to their approach to empathy and morality? Do women possess inherent qualities that help, most of the time, manage leadership and power more ethically and efficiently?

Among the various risk factors for antisocial behavior, “being male” stands out as a particularly strong predictor. Both biological and socio-cultural factors are involved in the formation of these morally relevant gender differences.

Interdependent vs. independent?

Studies show that the majority of women are more likely to be socialized to see themselves as interdependent with others – and therefore also more attuned to relationships and the emotions of other people.

By contrast, most men are often raised to be more independent. As a result, leading psychologists suggest that most women integrate moral values more deeply into their identities than men, because morality facilitates relationship building. This leads most women to prioritize values that promote the welfare of others.

Looking beyond socializing influences

However, beyond socializing influences, numerous genetic and hormonal differences between the sexes also play a crucial role and should not be overlooked. Among the genetic factors that increase the risk for antisocial behavior, the monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene is the most well-supported by research.

Variants of the MAOA gene, notably the low-activity allele, are associated with an increased propensity for violence and antisocial behavior when its carriers are reared in adverse environments.

MAOA is an X-linked gene. Because males have only one X chromosome, they are more affected by mutations causing low enzyme activity. In contrast, females have two X chromosomes and can compensate by deactivating one.

Twice as likely to exhibit aggressive behavior

Studies demonstrate that individuals with the low-activity allele of this gene are twice as likely to exhibit aggressive behavior under social exclusion than those with the high- activity variant.

These findings highlight the interplay between genetic predispositions and environmental factors in shaping moral behavior. In particular, they show that most males are prone to anger and aggression when these genetic factors and adverse environmental influences converge.

Hormonal factors and a higher propensity for antisocial behavior

Similarly, some hormonal factors contribute to a higher propensity for antisocial behavior among some men. Testosterone, for example, is commonly linked to negative behaviors like aggression and dominance.

Higher levels of testosterone are generally found in men and correlate with more egocentric behavior.

Men as status seekers

However, while initial studies suggested a direct link between testosterone and aggression, later research indicates that testosterone might not increase aggression per se, but rather the motivation to achieve and maintain social status.

In certain contexts, this pursuit of status can motivate anti-social behavior. Moreover, evidence points to a role for testosterone in both physical and non-physical aggression.

Testosterone and insider games

Nevertheless, studies also show that high testosterone levels can translate into parochial altruism, meaning favorable treatment of ingroup members and a mix of positive, neutral or negative attitudes towards the outer group, depending on perceived emotional self-interest.

In other words, testosterone is associated with both aggressive and cooperative behavior, depending on group membership, competition and interest.

What is clear, however, is that high levels of endogenous testosterone tend to drive dominance-oriented behaviors, which helps to explain why some men are more inclined to seek positions of power, although not necessarily for the wrong or selfish reasons.

The drive for power…

While men may be more likely to strive for power, they appear to be predisposed – genetically, hormonally, and through social conditioning – to exhibit more self-centered behavior in most circumstances.

Men are socialized to adopt self-serving behaviors, although there are exceptions. Higher testosterone levels and some genetic predisposition (i.e. the MAOA gene) may make them more prone to egocentric exercises of power, but not necessarily in a negative way.

… vs. prioritizing the welfare of others

Conversely, most women are often (though not always) socialized to prioritize the welfare of others and are therefore more likely to exemplify the positive, socialized face of power.

That said, this field of study is still underexplored, which means that conclusions cannot yet be drawn with a high degree of evidence.

Toward the frontiers of research

Adding to the complexity, recent findings indicate sex differences in how the brain’s reward pathways function, particularly in the hippocampus and nucleus accumbens.

Males and females employ different molecular mechanisms to strengthen these neural connections, although more research is also required in this space.

Research shows that in some circumstances, most women tend to exercise power with a heightened concern for others’ welfare compared to most men.

Male and female leaders who are empathetic are more likely to create policies and make decisions that are fair and beneficial to wider segments of society.

This can result in more inclusive and compassionate governance, and is a potent reminder that, like it or not, politics cannot be divorced from emotion.

The moderating role of cultural, historical and even economic factors

In exploring the associations between power, gender and morality, we must not overlook the moderating role of cultural, historical and even economic factors.

Cross-cultural psychology has identified the cultural context as key to influencing the moral development of individuals. Shaped by factors such as history, social frameworks, cumulative memory and institutional regulations, each culture develops a unique value system that is transmitted across generations and shapes individuals’ moral reasoning.

Gender-related differences in moral judgments persist across cultures

Interestingly, several studies suggest that gender-related differences in moral judgments persist across all cultures and may sometimes be even more influential than cultural factors.

A study comparing Eastern (i.e., Russian) and Western (i.e., U.S., UK, Canadian) subjects found that men in both cultures delivered more utilitarian judgments than women.

At the same time, the study observed that men from Western cultures were more utilitarian than Russian men, while no significant differences were observed among women.

Some degree of gender-related universality

These findings suggest some degree of gender-related universality across cultures, while also acknowledging some slight culture-specific variations in moral outlooks.

Importantly, culture not only shapes individuals’ moral values, but also how power is understood and manifested in various societies.

One study, for example, found that gender differences in managers’ ethics become more pronounced under the cultural dimensions of collectivism, humane orientation, performance orientation and gender egalitarianism.

Such findings underscore the role of culture in shaping gender-related differences in moral judgments made by individuals in positions of power.

Economic factors are crucial

In a similar vein, economic factors are crucial in mediating the relationship between power, morality and gender. Some evidence suggests that when financial incentives to cheat are significant, women may be just as likely as men to prioritize profit over morality.

Overall, these findings show that men and women are not merely the sum of their genetic, neural and hormonal predispositions but also heavily influenced by legal, social, cultural, economic and especially personal experiences.

Men less well equipped to wield leadership and power ethically?

So, are most men less equipped than most women to wield leadership and power ethically?

Research has shown that the majority of men tend to be more assertive and independent (and most women more relational or affiliative) in their moral judgments, but not necessarily less ethical.

However, some scholars make a strong case that a blend of both instrumental and expressive traits can lead to optimal moral outcomes and more effective leadership.

Leadership decisions are not made in isolation: In today’s political landscape, good decisions balance hard and soft power, including both male and female inputs.

A brief excursion into neuroscience

Looking to the future, we should prioritize adapting decision-making processes to what we are increasingly finding out from neuroscience and neuropsychology, without being overly deterministic or reductionist.

In particular, it is crucial to understand key neuroscientific aspects about the nature of power.

Power, often perceived as the ability to realize one’s will, activates specific areas of the brain associated with the reward system, known as the mesolimbic system. It connects the ventral tegmental area in the midbrain to the ventral striatum of the basal ganglia.

The latter includes the nucleus accumbens and the olfactory tubercle. The mesolimbic system regulates incentive salience, motivation, learning, fear and other cognitive processes.

But power does not inevitably have negative effects on our behavior. Rather, higher levels of power are associated with increased confidence and enhanced cognitive abilities. That may further increase the successes of powerholders.

This phenomenon is known as the “Winner Effect,” which empowers us to succeed through positive power-induced brain changes.

Complexity demands continued research

The exploration of the links between power, morality and gender continues to uncover layers of complexity that demand continued research.

In light of recent findings, more attention needs to be given to a wide range of legal, biological, social, cultural, personal, historical and economic factors involved in shaping morally relevant gender differences in attitudes towards power.

While it is critical to avoid generalizations, it is likely that women have the ability to bring unique perspectives and strengths to ethical leadership and governance structures. These may not necessarily be better, but rather complementary.

Needless to say, there is also still a lot more that can – and should – be done to promote women in positions of power and leverage the unique perspectives and strengths that they bring to leadership roles.

Hierarchical power structures transcending the male/female divide

Above all, we need to get to grips with issues at the heart of hierarchical power structures that transcend the male/female divide in politics as well as academia, civil society and the corporate world.

At the same time, we need to keep in mind that it is a bitter irony that the skills most needed to obtain power and leading effectively are the very qualities that deteriorate once we hold power, regardless of gender.

Decline in empathy and immoral behavior

This decline in empathy and social abilities in men and women is associated in some circumstances with immoral behavior. While leadership and power can enhance certain qualities necessary for success, in some poorly structured situations power may be associated with tendencies toward overconfidence and self-centeredness, in both men and women.

As a result, power may undermine critical preconditions of effective leadership: Namely the ability to empathize and respond to people’s needs.

Conclusion

Of course, this does not mean that women are immune from rigid, unethical or less empathetic leadership styles within various power structures. Nor does it mean that men are less likely to manage leadership and power positions with great responsibility, empathy, ethics, morality and efficacy.

But it is important to note these predispositions as pivotal factors. We also need to acknowledge that they play second fiddle to solid governance structures. What matters greatly in all societal frameworks, political and non-political, is for them to be propped up by proper vetting, capabilities, accountability and consensus, for both men and women.

Takeaways

Do women possess inherent qualities that help, most of the time, manage leadership and power more ethically and efficiently?

The perceived strengths and weaknesses of top-level women decision-makers have long sparked debates about their rise and eventual fall. The current US presidential campaign, which is pitting a woman against a man, has brought the issue into sharp focus.

We would be well served to look to neurobiology and neuropsychology to help us understand the foundations of responsible leadership and the relationship between gender, power and morality.

Leading psychologists suggest that some women integrate moral values more deeply into their identities than men, because morality facilitates relationship building.

While men may be more likely to strive for power, they appear to be predisposed - genetically, hormonally, and through social conditioning - to exhibit more self- centered behavior.

In most circumstances, most men are socialized to adopt self-serving behaviors, while most women are typically socialized to prioritize the welfare of others. This may lead women to exemplify the positive, socialized face of power.

Leaders who are empathetic are more likely to create policies and make decisions that are fair and beneficial to wider segments of society. This can result in more inclusive and compassionate governance.

Men and women are not merely the sum of their genetic, neural and hormonal predispositions but also heavily influenced by personal, legal, social, cultural and even economic factors.

We need to get to grips with issues at the heart of hierarchical power structures that transcend the male/female divide in politics and the bitter irony that the skills most needed to obtain power and lead effectively, may in certain circumstances become the very qualities that deteriorate once we hold power.

A Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) from the Global Ideas Center

You may quote from this text, provided you mention the name of the author and reference it as a new Strategic Intervention Paper (SIP) published by the Global Ideas Center in Berlin on The Globalist.