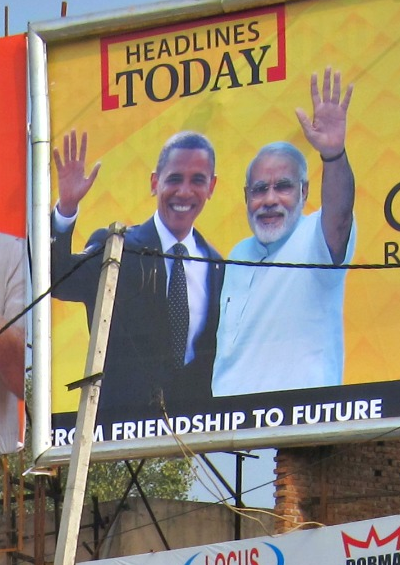

Can Modi Copy Deng?

India’s leadership needs to change, modeling China may be the answer.

January 27, 2015

The thought of Modi, an original and innovative doer if ever there was one, copying anyone seems so implausible that the first instinct is to perish the thought at birth. But it is interesting to list how Modi could “do a Deng” for India.

Deng Xiaoping inherited a China wracked by the inefficiencies of Communism. Five decades of communism had deadened the innately entrepreneurial spirit of the Chinese people.

But Deng also inherited a China blessed by the upside of communism, which had created a highly disciplined party cadre across the country. This body of people is indeed much like India’s bureaucracy, except for one crucial difference: the Chinese Communist Party basically marches to a single drumbeat.

That “drummer” is the country’s President/General Secretary/Chairman – Deng then, Xi now. In contrast, the Indian bureaucracy is a discordant orchestra with multiple political conductors.

Mao built his Party cadres to weed out all those who either were, or could become, dissenters to his thoughts. Deng used the very same party to unleash the Chinese “animal spirits.”

And municipalities and provinces in China compete viciously with each other to achieve the highest growth numbers in a no-holds-barred, single-minded commitment to the bottom line.

Can Modi do a Deng for India?

Unlike China, India is a soft state. Our citizens live in an asymmetric economic and political environment. On average, our citizens are as economically deprived as the Chinese were.

Even so, they have also become accustomed to significant levels of personal and political freedom that are more typical of a developed democracy. Significant interest groups all receive a special package of subsidies tailored just for them.

That package may not be very substantial in an individual context. And it may be threatened by inflation and increasing public fiscal stress. The important thing is that it exists – as a symbol that the (Indian) state “cares.”

This has led to a significant problem in India’s domestic political economy. Citizens often vote as a reflection, or in anticipation, of subsidies received from whichever political party or government.

The only way of getting Indian citizens to vote beyond subsidies is to rapidly enhance their individual incomes to a level where largely stagnating subsidies no longer mean much. For this to happen, private sector jobs based growth is the key.

Global economy forces India’s hand

Unfortunately, the world economic environment is now even less supportive of inefficient economies than it was in the “go-go years” until 2008. India remains a hugely inefficient economy because of the high transaction cost of doing business, even for domestic entrepreneurs. Some of this is due to a very inefficient and decentralized but systemic corruption.

What can Modi do considering all these circumstances?

The most fundamental achievement he has to accomplish is to significantly increase transparency and depoliticize economic regulation.

This can be achieved by one simple step – transferring powers to autonomous, technical regulators. No other measure has the clear-cut potential to vastly reduce the space for India’s brand of “crony capitalism.”

That aside, five other fundamental institutional changes are required so that Team Modi can really target poverty, enhance growth and increase private sector employment.

First, Modi has to radically change the manner in which appointments are done at the Union government level in Delhi. The most important step is to adopt a merit based system.

The PMO – the prime minister’s office – urgently needs to have an HR department as an anchor. Its purpose is to identify and track potential officers for the senior-most positions, using a variety of indicators.

Mind you, it is said with good reason that the most powerful institution in China is the personnel office of the CCP.

Second, to improve the effectiveness of India’s government, while preserving its diversity, Modi has to ruthlessly prune the political executive and the bureaucracy of any and all elements who are, or have been, ineffective or complicit in corruption.

This is not about launching a witch hunt for the corrupt. It is more about identifying effective politicians and bureaucrats (of which individually there is an oversupply) and putting them in the right positions.

Uniting national leadership

Third, India is not governed from Delhi alone. That is why Modi has to corral those Chief Ministers of all states that are similarly inclined to pursuing a growth strategy.

Some, but not all, of these top elected politicians hail from BJP governments. But the real issue here is to form alliances, not for political survival, as was the practice in the past, but for national growth.

Indians must urgently realize that it is in the nature of network economies that they create spillovers across state boundaries. Businesses pay great attention to such opportunities, since they prefer to locate where land is cheap, labor is abundant and they can rely on a pre-existing infrastructure nearby.

Andhra Pradesh’s Chief Minister Naidu previously used this model of cross border spillovers from Karnataka and Tamil Nadu to his state’s benefit. Western UP and Haryana have similarly benefited from the economic dynamism of Delhi, remarkably irrespective of what their State Governments were up to.

This shows that it is actually not necessary to have every chief minister on Team Modi’s bench. Just getting 50% onboard, sprinkled across the country, can generate strong growth impulses nationally.

Fourth, the key administrative unit, where the proverbial rubber hits the road, are India’s 604 Districts in rural areas and around 3255 “towns.” It is at this level that all reform and change is implemented.

Unfortunately, this level of administration remains completely divorced from any direct responsibility by the Union-level government for achieving the three point agenda of growth, jobs and poverty reduction in their own areas.

This disconnectedness has to change if we Indians ever want to “Do a Deng.” This is not that difficult: China determines local targets for national objectives. We must do the same.

Deng he is not

Among many other steps that need to be taken in that regard, technical competence and gravitas need to be restored to district and local body administrations. Today, local “planning” is more about appeasement of local politicians rather than about achieving national objectives.

That is why every District and Town will also need base line studies of jobs, poverty levels and the size of the local economy. Their annual growth and poverty reduction targets and achievements must be available publicly to create a clear sense of accountability.

China’s system of promotions up to the next higher level of the administrative ladder is based on past performance and the gravity of the problems mastered. There is a lesson in that for India as well.

Prime Minister Modi does not have a centralized Party-based executive to rely upon, as Deng did. But, in keeping with India’s virtues and traditions, he can – and he must – forge a team of politicians, bureaucrats and non-government professionals who have a passion for lifting India out of poverty via economic growth and private sector jobs. Many are waiting for his call.

Takeaways

Could Modi “do a Deng” for India?

Unlike China, India is a soft state. Our citizens live in an asymmetric economic and political environment.

India remains a hugely inefficient economy because of the high transaction cost of doing business.

Modi has to corral those Chief Ministers of all states that are similarly inclined to pursuing a growth strategy.

Modi must forge a team of politicians who have a passion for lifting India out of poverty via economic growth.