China’s Battle Against Corruption Gets Serious

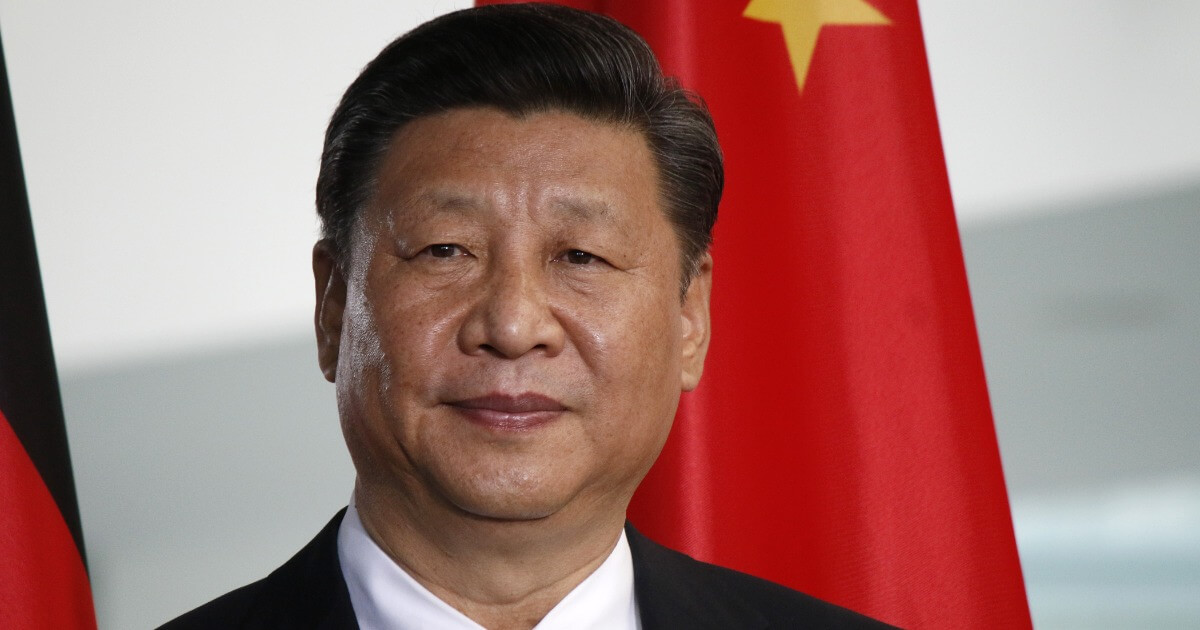

China’s Xi follows anti-corruption textbook, but still has a way to go.

July 30, 2014

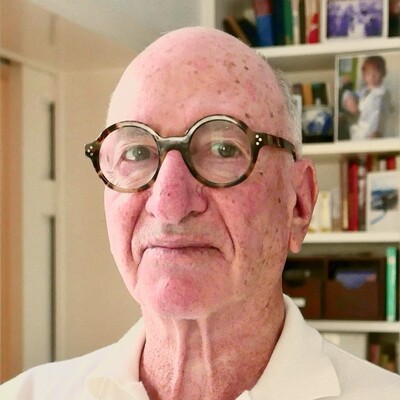

In his determined efforts to fight corruption, China’s President Xi Jinping is following the textbook to the letter. His guru could well be Professor Robert Klitgaard, now at Claremont Graduate University in California.

As the distinguished South African academic has written, there are three rules to be followed in a successful campaign against corruption:

1. “Put the fight against corruption at the center of creating a new government.”

2. “Create a core of qualified well-paid government leaders.”

3. “Demonstrate that impunity is over by frying some big fish.”

And this is where the current news is so encouraging. Few fish (although Xi and the Chinese press prefer to say “tiger”) are bigger in China than Zhou Yongkang. The Chinese official media has reported that the 71-year-old Zhou has been arrested. He is now being investigated by the government’s anti-corruption agency, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection.

Zhou is the first former member of the Politburo to be arrested in China in many decades. For five years until he retired in 2012, he was the nation’s chief of security. In that capacity, he directed China’s police and intelligence services.

He also had enormous power over large parts of industry, notably in the energy sector as well. As an omen of what was to come, a number of his subordinates had been arrested in recent months.

True to the Klitgaard script, Xi has placed loyal and skilled officials at the Central Commission. That demonstrates that no individual, however powerful and senior in the Chinese Communist Party, is above the law.

By going after a number of top level officials and stripping them of their influence, Xi is not just asserting his authority and sending out powerful signals. He is, in effect, creating a new government.

Long overdue attack

The attack on corruption in China is long overdue. Corruption is rampant. Many government and Communist Party officials enjoy great wealth. And they have long placed wives and sons and daughters and other relatives in key business positions that have assured them of formidable fortunes.

The arrest of Zhou will rattle the nerves of officials and Party members across China. They will be asking: who will be next? They will be replacing Rolex watches with cheap time-pieces and ensuring that they are not seen shopping at the many top luxury Western stores that abound in Beijing, Shanghai and other cities.

But ordinary Chinese citizens, who are likely to welcome the anti-corruption drive, may still be skeptical. They may wonder if this is just a purge by Xi of actual and potential political opponents, rather than a sincere long-term effort to eradicate corruption.

To convince people in China and abroad that he is determined, Xi needs to embark not only on high-profile arrests, but also on fundamental public policy changes, starting with the legal system.

Why the secrecy?

The current Chinese system enables Xi to be the public prosecutor, the jury and the judge at the same time. Moreover, all of these roles can be played in secrecy.

Everyone who is accused of a crime in China knows that he will almost certainly be found guilty. And so it will be with Zhou. He has scant opportunity to protest his innocence. He may not be able to select his own defense. His trial is likely to be in secret. In short, there is no due process.

So far, Xi has shown no inclination to change the legal system. Nor has he indicated a willingness to start making government activities transparent and so make government and Party officials publicly accountable.

The details of most public procurement contracts are not published, yet decisions by officials on who wins contracts and on what terms are prone to bribery when shrouded in secrecy.

Next, there is considerable opacity when it comes to the taking of gifts by government officials and Party members. Not only do business people regularly provide gifts to officials, but gift giving is remarkably also often the way in which lower level officials ingratiate themselves with superiors — and manage to climb the power ladder.

The Chinese people also have no idea about the compensation levels of senior officials and Party members. That means they have no way to determine if the life styles of these officials is commensurate with their official incomes.

This underscores why transparency across almost all aspects of government practices is essential if Xi is serious about ending impunity. If he wants to know about how to get this job done, Professor Klitgaard has many pragmatic ideas to share.

Takeaways

The battle to root out corruption in China has begun, says cofounder of Transparency International.

After the latest arrest, Communist Party officials across China nervously ask: who will be next?

China’s battle against corruption means fewer Rolex watches and reduced sales at Western luxury stores in Beijing.

Read previous

Hedge Funds as Bottom Fishers

July 30, 2014