Crimea: What Could Have Been

Vasily Aksenov’s 1979 utopian novel “The Island of Crimea” in today’s context

March 16, 2014

This is the second time in history that Crimea has seized global attention. Previously, it was in 1853, at the start of the Crimean War. Notably, that was a time when Russia got its clock cleaned on the battlefield by the combined power of the British Empire, Second French Empire and Ottoman Empire. No wonder, then, Crimea holds a special meaning in Russia’s collective psyche.

Beyond the military frame of the Black Sea machinations of Europe’s great powers, there is another episode to be reported. Although it is a literary one, it is no less meaningful in the current political context.

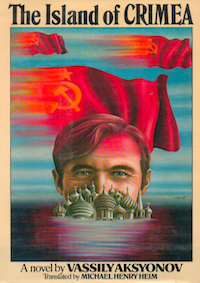

In 1979, Soviet dissident writer Vasily Aksenov wrote a utopian novel The Island of Crimea. It was based on a fantasy that Crimea was an island that had managed to break away from the Soviet Union during the Russian Civil War. Over time, it had become a free-wheeling, multicultural, open and prosperous democracy.

Soviet-era Crimea

The real geography and history of Crimea, of course, was quite different. To start with, Crimea is not an island, but a peninsula. It juts out into the Black Sea and is linked to the mainland by the narrow Isthmus of Perekop. The Red Army entered it in 1920.

In 1954, although Crimea was then mostly populated by Russian settlers, then-Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev transferred it from Russia to Ukraine. It was a purely administrative decision, since Khrushchev could never conceive of Russia and Ukraine parting ways.

Nor could Aksenov imagine anything of the kind back in 1979. During the Soviet era, Crimea was an intensely beautiful summer resort. It was freer, more free-wheeling and easy-going than grim and grey Moscow or Leningrad.

But it was still a dingy Soviet place, offering dilapidated sanatoria (resorts) for the proletariat and camp beds for rent in private homes for vacationers.

Looking to Taiwan

When looking for a real-world model for his utopian Crimea, Aksenov took the island of Taiwan, which avoided a communist takeover in the Chinese Civil War and became a technologically advanced, prosperous and, eventually, democratic state.

The Kuomintang-led government decamped to Taiwan when it lost control of the mainland in 1949. Thereafter, the island was governed directly through the National Assembly, a legislative body supposedly representing all of China — not just Taiwan. The institution survived under this fiction until 2005.

The KMT army also fled to Taiwan, and it dominated the “national” government in its island exile as a military dictatorship in the early post-Civil War decades.

While China still regards Taiwan as its breakaway province, in Taiwan, there has been a push in recent years to declare outright independence. The idea is supported by a majority of Taiwanese. However, Beijing is adamantly opposed to any such steps.

But what do Aksenov’s utopian novel and the present grim geopolitical reality have in common?

The last stand of the southern White Army

Crimea did at one brief point look very similar to what Taiwan came to be in the 1950s. By 1920, the Bolsheviks were clearly winning the Civil War in Russia and had asserted control over most of the former empire. Lots of people all over the vast Russian Empire had reason to fear Lenin and his cohorts.

Meanwhile, noblemen, landowners, businessmen, clergy, urban professionals and ordinary middle class people had found refuge in Crimea. That was also the location to which the White Army — the largest resistance faction to the communist Red Army’s takeover — had retreated. It was commanded by Baron Wrangel, who was also the head of the government.

But, unlike the KMT in Taiwan, the Whites were not able to hold Crimea. Some 140,000 anti-Bolshevik White refugees following Wrangel were evacuated by sea and subsequently dispersed throughout Europe. 50,000 White Army officers who stayed behind, trusting in the Bolsheviks’ reassurances, were subsequently massacred on Lenin’s orders.

The precarious statelet

Taiwan has a varied population, consisting of early Han Chinese migrants, refugees from the mainland and their descendants and about half a million indigenous people. The latter belong to an Austronesian ethnic group related to inhabitants of the Philippines, Malaysia and other Pacific Rim countries.

In Crimea, the original population was Crimean Tatars, who were collectively deported to Central Asia in 1943, allegedly for welcoming German occupiers. They were allowed to return only after communism collapsed and now make up less than 15% of the region’s population.

While China never relinquished its claim on Taiwan, Russia parted with Crimea with relative ease. In 1994, Russia even joined with the United States and Great Britain to guarantee Ukraine’s territorial integrity in exchange for Kiev’s agreement to give up Soviet-era nuclear weapons that remained on its territory.

But in Aksenov’s novel, the independent Crimea finally comes to a bad end when Moscow decides it no longer wants to tolerate a free and prosperous capitalist statelet so close to its borders.

Staging a military operation eerily prescient of Vladimir Putin’s underhanded invasion, the Soviet Army of the story occupies Crimea. Most of the novel’s protagonists get killed.

Takeaways

Imagine Crimea had managed to break away from the Soviet Union to become an open and prosperous democracy.

The real-world model for Aksenov’s utopian Crimea was the island of Taiwan, which avoided communist capture in 1948.

In 1920, noblemen, landowners, urban professionals & middle class people really did flee from the Soviets to Crimea.

Staging an operation eerily prescient of Putin's underhanded invasion, the Soviet Army occupies Crimea of the novel.