Curbing Gang Violence in Central America

What should the United States be doing to rein in Central American gang violence?

July 6, 2013

As July 4th passes, a day in which U.S. patriots show pride in their country, it may be worth reflecting on where the United States and other governments may have fallen below their own standards of social justice.

The relevant question is to consider how they may rectify the situation.

Exploring the issue of gang violence across the Americas — an increasingly serious social problem — provides such an opportunity.

Gang violence, fueled by the drug traffic in Latin America, Central America and the Caribbean, is having a serious effect on people’s lives. Most poignantly, it threatens to alter the social fabric of the countries in the region.

Central American gangs, also called maras are named after the voracious ants known as marabuntas.

The gangs are involved in a wide range of criminal activities, such as arms and drug trafficking, kidnapping, human trafficking, people smuggling and illegal immigration.

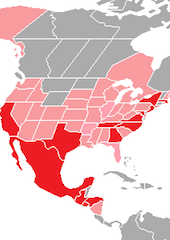

One of the best-known Central American gangs, Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13, has an estimated 70,000 members that are active in urban and suburban areas across North America.

It originated in Los Angeles in the 1960s and then spread to other parts of the United States, Canada, Mexico and Central America.

The gang’s activities have caught the attention of the FBI and the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which have conducted raids and arrested hundreds of gang members.

The FBI called MS-13 “America’s most violent gang.” It has been particularly active in Los Angeles County, the San Francisco Bay Area, Washington, D.C., Long Island, New York, and the Boston area.

Their code of conduct includes fierce revenge and cruel retributions. Members of this gang were originally recruited by the Sinaloa in their battle against the Los Zetas Mexican cartel in their ongoing drug war south of the U.S. border.

Many gang members living in the United States have been deported back to El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala.

To Americans, that may look like a problem solved. In reality though, it only adds to the already serious social problems in those countries.

The returning gang members bring back with them crack cocaine. Predictably, drug-related crimes are soon on a steep increase.

Those gang members deported from the United States enlarge the local groups and find easy recruits among the local disenfranchised youth. Today, most of the members are in their twenties, while their leaders are in the late 30s and 40s.

The gangs’ battles with the police for control of working-class neighborhoods involve in each case heavy-handed tactics by the police.

They also prove unproductive, since they unleash more random violence and terror.

As an almost logical result of each government’s efforts to eliminate them, many gang members have but one incentive — return to the United States.

There, they continue their involvement in criminal activities. And so the vicious cycle begins anew.

Today, the gangs have expanded into southern Mexico, Colombia and Brazil. This arouses calls for a more organized effort to combat them.

Because of the great loss of the lives violence causes, the Pan American Health Organization and also the World Assembly of the World Health Organization have defined violence as a “public health problem.”

They proposed an epidemiological approach to address it that consists of

- Defining the problem and gathering information

- Identifying causes and risk factors,

- Developing and trying out specific interventions

- Evaluating policies’ effectiveness.

In the past, this approach was used successfully in Colombia. There, in the 1990s, an agreement was signed between government officials and the leaders of gangs that had been operating in the city of Cali.

As a result, the gangs’ leaders stopped their criminal activities and the government officials made a commitment to provide loans and technical training to gang members so that they might become productive members of society.

A similar approach is now being used in El Salvador.

There, the government is trying to curb gang activity through an ambitious jobs program.

This is complemented by other social measures, such as training and provision of jobs that could be followed by the other countries in the region.

Successful approaches suggest that controlling gang violence demands long-term action, even when it might not show immediate results.

Prevention activities must also be targeted at the youngest sectors of the population, particularly those suffering from abusive conditions at home. After all, gang violence is often the direct result of poverty and no formal education.

Among these actions to be taken is providing job training and psychological assistance, as well as job opportunities and loans to those youngsters.

The use of a multifaceted approach may be the best guarantor against the social scourge of gang violence in the Central American region.

Takeaways

Many gang members living in the U.S. have been deported, fueling serious social problems in their home countries.

Offering job training, loans and mental health help to youngsters may be the best counter-measure.

Controlling gang violence demands long-term action, even when it might not show immediate results.

Gang violence threatens to alter the social fabric of the countries in the region.

Read previous

Francis Scott Key and the Slavery Question

July 5, 2013