Dateline 2014: Turkey Joins the EU (Part I)

What might the international reaction be to a European Union that includes Turkey?

May 14, 2007

Brussels, Belgium, January 1, 2014 — Turkey's membership was celebrated by thousands gathered in Sultanahmet and Taksim squares in Istanbul last night. The lively crowds were chanting songs and waving EU flags.

Both squares were decorated with Turkish and EU flags and pictures of Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey — in addition to hundreds of signs of various colors, sizes and messages.

The most significant message was a neon spot placed on a suspended sign between the two minarets of the Saint Sophie (Aya Sofya), which read, "WELCOME EU."

The Saint Sophie, which was originally built as a church by a Byzantine emperor, then transformed into a mosque following the conquest of Istanbul by the Turks in 1453 with the addition of four minarets — and finally converted into a museum in 1935 — has a special significance for this particular occasion.

Nothing could better symbolize the union of the EU and Turkey than this historical place of worship that united Christianity and Islam centuries ago.

Joining the EU has not been easy for any country, as the privilege of becoming a club member required compliance with strict economic and political requirements set by the EU's existing members.

Turkey's European journey turned out to be significantly bumpier than others because of its religion, size and history. Turkey has made remarkable progress on all fronts since the EU's decision declaring Turkey's candidacy for full membership in 1999, due mostly to the impetus provided by the start of negotiations.

Turkey's achievements vis-à-vis improving its democracy, the removal of practical barriers against its minorities, both ethnic and religious, as well as reducing the military's role in politics have been monumental.

One of the most impressive achievements has been the substantial increase in per capita income recorded as a result of the continuous high growth rates Turkey’s economy has enjoyed over the last ten years.

As of the end of 2013, Turkey's per capita GDP reached $20,200, slightly above 50% of the EU average, which stands at $39,500 as of September 2013. With Turkey joining, the EU is now the second-largest economic bloc after NAFTA, with a population of over 570 million.

Turkey, as the 30th member of the EU following the accession of Croatia and Macedonia last year, has not been granted some of the benefits enjoyed by the countries previously admitted to the union.

The two most significant ones are related to the free movement of labor and agricultural subsidies. Turkish workers, except those trained in fields determined by each member country, will not be granted free movement until 2021. Thereafter, the restriction will be gradually lifted because aging populations in most EU countries will increase the EU's need for Turkish labor.

According to EU officials, Turkey's progress in areas such as agricultural subsidies, environmental adjustment policies, measures against the informal economy and furthering of judicial reforms will be closely monitored by the European Commission during the first three years of membership.

The EU membership has evidently relieved the tension in Turkish society, and assured Turks that their two most sensitive concerns — namely separatism and Islamist fundamentalism, are going to be better addressed with their country's membership in the EU.

For a long time, many euro-skeptic Turks had argued that the EU's aim was to divide the country and let the Islamists control it. Also, the long-lasting "identity" issue — whether Turkey is western or eastern/Muslim — appears to be resolved, at least for the time being.

Observers believe that the remaining cynicism will fade away as Turkey is further integrated with the EU. Such a consensus could not have been reached in the absence of the constructive and engaging attitudes of the new generation of European politicians, who were scarce until very recently.

Turkey's membership had been in grave doubt almost a decade ago following the rejection in 2005 of the new European constitution by France and the Netherlands, two of the EU's founding members.

In addition to the uncertainty created by this rejection, the coming to power of Angela Merkel in Germany and Nicolas Sarkozy in France had cast doubts over Turkey's European aspirations.

Both leaders had advocated for a "privileged partnership" with Turkey. However, the substance of the proposed partnership had never been made public, and was widely viewed as a tactical move to derail Turkey's membership.

Editor’s note: Read Part II here.

Read previous

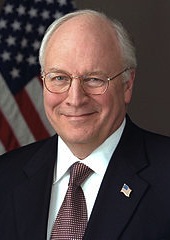

Redeeming Cheney

May 9, 2007