Francis Scott Key and the Slavery Question

What role did the famous author of “The Star-Spangled Banner” play in the debate over American slavery?

July 5, 2013

One hundred and eighty or so years ago, the paths of three men crossed in Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. The most famous of the three was Francis Scott Key.

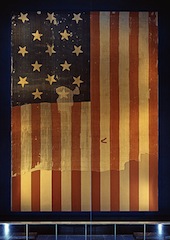

He was the scion of Maryland’s slave-holding aristocracy and is famous for having written “The Star Spangled Banner.”

When the three men’s paths crossed, Key was the District Attorney of the City of Washington, a prestigious post.

The most enterprising of the three men was Beverly Randolph Snow, an Epicurean chef of mixed race heritage. He had bought his way out of slavery and came to Washington to seek his fortune.

Long before the contemporary age of ego-driven chefs, Snow called himself the “National Restaurateur.”

The unluckiest of the three was John Arthur Bowen, a nineteen-year-old boy, a slave, whom Key charged with attempted murder in 1835. The lives of these three men intersected on the streets of Washington, D.C.

Francis Scott Key was politically ambitious and religiously observant. He was no Epicurean, renouncing luxury in all of its forms. Yet he, too, ate at Mr. Snow’s restaurant at the corner of Sixth and Pennsylvania, which was known as “the Epicurean Eating House.”

Snow’s place offered a natural rendezvous for Key and his political associates. They were lawyers practicing in the courthouse up the street, western land speculators visiting the capital on business and innumerable congressmen living in the boarding houses.

Mr. Key respected Snow, the restaurant’s mulatto proprietor, even if he did not always like his ostentatious style.

Key prided himself as a humanitarian. As a young lawyer, he had relished defending individual colored people in court. Some even called him “the Blacks’ lawyer.”

By 1835, in the timeless ways of Washington, Key had parlayed his law practice into political connections with the network of editors, landowners and slave masters around General Andrew Jackson.

In 1833, President Jackson rewarded Key with the office of District Attorney. Key had reached a pinnacle of the political power.

But it was in a time of trouble in the United States. In the 1830s, small groups of Americans, white and black, started calling for the immediate abolition of slavery. For some Americans, this was a threatening message.

In 1835 alone, the 25 states experienced no less than 53 riots, almost all related to issues of race. Most involved attacks by mobs of white men on free blacks and white anti-slavery speakers.

The violence of the summer of 1835 forged a new notion in American life, at least in the northern states: that defending the republic required opposing the slave masters of the south.

At the beginning of the year, there were 200 anti-slavery societies across the northern tier of the country. At the end, 527. By 1837, there were 1,000.

A “Snow-Storm” with national implications

In this cataclysm, the paths of Francis Scott Key, Beverly Snow and Arthur Bowen crossed.

In Washington City, the events started when 19-year-old Arthur Bowen, servant in the home of Anna Thornton, attended a clandestine “talking society.” There, young enslaved men talked among themselves about slavery and what they could do about it.

After the meeting broke up, Arthur and a friend continued to talk and drink in Lafayette Park, across the street from the presidential mansion.

Returning home, Arthur groped in the dark, picked up an axe that he cradled in his arm and mistakenly entered the bedroom where his owner Mrs. Thornton, her mother and his own mother, also Mrs. Thornton’s slave, were sleeping.

Whatever Arthur intended in his inebriated state, the startled women woke up the whole neighborhood, which resulted in a manhunt for Arthur and his eventual incarceration. This one event had many ramifications for many lives.

The events of August 1835 would soon be dubbed the “Snow Riot” or the “Snow-Storm” in recognition of the central role that Beverly Snow’s singular personality played in igniting popular passion.

In the shocking news of Arthur Bowen’s alleged attack on Mrs. Thornton, many a white man saw signs of an incipient slave rebellion.

Crowds of white men converged on the City Jail in Judiciary Square calling for the head of Arthur Bowen. When they couldn’t get their hands on him, they turned on Beverly Snow, the capital’s restaurateur and best-known free man of color.

Snow’s notoriety as well as his success did not sit well with many whites. Nevertheless, amid the tumult, Anna Thornton — in acts that were very brave for those days — made every effort to save Arthur Bowen.

The famous Mr. Key had a different agenda. He was a loyal lieutenant of President Jackson, whose supporters had famously taken over Washington from day one and who himself was an unapologetic supporter of slavery.

Key personally prosecuted the case against Arthur Bowen, which he won, and then went after the rioters during the Snow-Storm in August 1835.

Key wanted to reestablish law and order in the nation’s capital and protect the white man’s right to own property in people. The constitution, in Key’s view, required no less.

In the spring of 1836, Key also brought charges against Reuben Crandall, a New York doctor who had brought abolitionist pamphlets to Washington.

The courtroom debate in U.S. v. Reuben Crandall crystallized how new ideas of rights introduced by the free people of color and their white allies had galvanized popular thinking in the mid-1830s.

The anti-slavery movement had forced three radical ideas into the realm of American politics: no property in people, multiracial citizenship and the freedom to advocate for both.

The audacity of those ideas was effective. In the 1820s, the organized anti-slavery movement in the United States was still very much on the margins. The idea of immediate emancipation caught on in 1830.

In the next five years, the abolitionists managed to establish Washington City as a battlefield for their cause by calling for the abolition of slavery in the nation’s capital.

From 1838 to 1839, the 25th U.S. Congress received almost 1,500 petitions signed by more than 100,000 people. Eighty percent supported the abolition of slavery in the capital. The tide would not be stemmed.

Francis Scott Key lost his bid to discredit the antislavery movement in the court of public opinion. The jury acquitted Crandall of all charges.

The defeat and family tragedies in 1835 sapped Key’s ambition. He resigned from the district attorney’s job in 1840, but remained a keen advocate of African colonization and sharp opponent of the antislavery movement. He died in January 1843.

Key’s life attests to the complicated and contradictory stances of people of the time. For years, Abraham Lincoln, too, favored colonization. However, as a young Congressman from Illinois, he also signed a petition to free the slaves in the District of Columbia.

The country would go on — and still goes on — to experience how very difficult it is to have a “land of the free and home of the brave.”

Go back to the first part of this essay.

Editor’s note: This essay is based on and contains excerpts from the author’s book, Snow-Storm in August, The Struggle for American Freedom and Washington’s Race Riot of 1835 (First Anchor Books, 2013). Copyright 2012 by Jefferson Morley.

Takeaways

The abolitionists established Washington as a battlefield by calling for the abolition of slavery in the nation's capital.

In 1835 alone, the 25 states experienced no less than 53 riots, almost all related to issues of race.

The violence of the summer of 1835 forged a new notion in American life, opposing the slave masters of the South.

In Arthur Bowen's action, many white men saw the signs of an incipient slave rebellion.

Key wanted to reestablish law and order and protect the white man's right to own property in people.