Freeing Poland From the Shackles of Its Debt Mountain

The story of how the transatlantic partners collaborated to help Poland secure a stable future.

June 3, 2014

This is a true story — one that harkens back to much brighter days in the transatlantic relationship. The story may be almost a quarter century old, but it has lost none of the meaning in the bigger scheme of things.

It is also a profoundly European story, one that underscores how much nations that were formerly at loggerheads for centuries can achieve with each other and for each other, if guided by a spirit of disciplined constructivism.

And it is finally a story of how the “invisible hand” can end up steering a lot of disparate parts, often unbeknownst to each other, and get them to a successful ending. Such an outcome requires the good will and energy on the part of many — as well as some strokes of sheer luck, as almost all good things that happen do.

Could you prepare a draft for us?

It’s early in the year 1990. The phone on the desk in my office rings. It’s a Capitol Hill staffer calling from across town.

“Hi there. I’ve got a question for you. Given your interest in the sovereign debt issue, the Senator is wondering whether you could help us. He wants to introduce a Sense of the U.S. Senate resolution to call on Western nations to forgive the debt that was piled up by Poland’s Communist-era governments. The question is: Could you prepare a draft for us?”

The invitation was exhilarating. I could do something meaningful for a good cause. It was really a no-brainer. Over the past ten years, I had observed the tremendous courage of the Polish people in standing up to the yoke of communism.

In the early 1980s, when martial law was imposed in Poland by the late General Wojciech Jaruzelski, who just died this May, I had been a law student in Bonn, then the German capital. I was friends with an American Ph.D. student who made several trips to deliver emergency supplies to Poland. She later became my wife.

In their unrelenting push to bring about an end of communism, which finally happened in 1990, the Poles did not just stand out for their courage in political and civic terms. They were also gutsy economically, keen on shedding as many of the disastrous remnants of Communist-era central planning as they possibly could.

As it turned out, they were also blessed with being able to rally around a common cause, despite their often sharply different political ideologies. This trait, in particular, explains the success of Poland (and the terrible failure of Ukraine so far).

Legacy of debt

To make true progress and create a sustainable path for economic reform and future prosperity, one step was very much needed: The new Polish reform government(s) should be freed from having to deal with one of the worst legacies of the country’s communist-era governments.

They had piled up a veritable debt mountain, money loaned to them by western governments and taken out to make life under communism more tolerable.

That had largely meant obtaining credit for consumption items, which did nothing to bring about the long-overdue transformation of the economy. Quite the opposite. It delayed the inevitable — and made the basic economics of the country worse.

As Poland’s GDP was falling precipitously after the end of the communist era and the launch of significant economic reforms, the country faced a double whammy. Its debt repayment obligations were staggering.

In dealing with the Latin American debt crisis of the early 1980s, the U.S. authorities maintained a tough stance toward debtor countries. The U.S. government was disinclined to permit any debt forgiveness, even though those loans had been made available to the borrower countries by money center banks, mainly based in New York City.

U.S. policymakers determined that the consequences of being more lenient in this case would have been highly problematic on many fronts.

While most of the debt of the U.S.’s southern neighbors was owed to private sector banks, most of Poland’s debt was owed to western governments. Better yet, the U.S. government’s share was considerably less than 10% of the total public debt outstanding.

That gave the U.S. Congress and the government considerable freedom of maneuver.

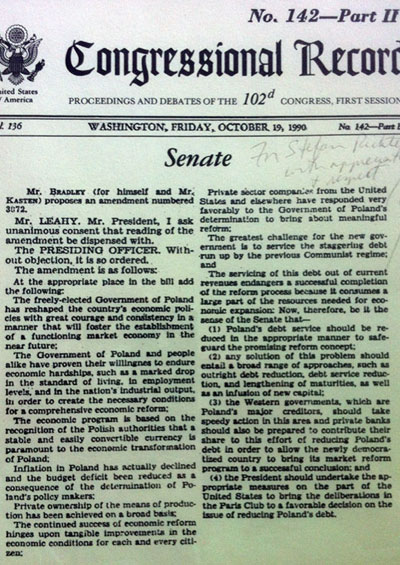

And so I, trained as a lawyer and having done a stint on Capitol Hill a few years earlier, sat down to draft the desired Sense of the Senate resolution. Mind you, these were the days before such conveniences as the Internet and online access to databases. So I drafted the resolution the old-fashioned way.

Well, at least I had a PC already, even though they were still operating with floppy disks, if my memory serves me correctly. I sent off my draft.

A framework for debt forgiveness

Soon after, the deed was done. The Senate resolution was agreed to. It made its way through the U.S. legislative process and had a very fruitful diplomatic impact. The U.S. government, keen on providing Poland with support, could now argue vis-à-vis other western nations that the Congress was pressing them to create a framework for debt forgiveness for Poland.

The Japanese were adamantly against any such move. The Germans, to whom by far the largest share of the debt was owed, were equally unenthusiastic. They worried about the Americans making international policy largely with other people’s money.

The French, usually in favor of debt forgiveness for poor countries, supported the Americans, but they wanted to be less generous than the Americans. Communist-era debt, the French reasoned in the Paris Club debates in 1991, should not get much more favorable treatment than post-colonial African nations who had gotten into deep water financially.

In the end, the Americans basically won. Half of Poland’s Communist-era debt was forgiven — and the payment terms stretched considerably. The reconstituted debt load was fully manageable for the new Poland under new management.

The ominous phone call

As the drafter of that Sense of the U.S. Senate resolution that was a critical part of getting the whole wave to move toward debt forgiveness, I have three more footnotes of history to report.

First, right after the Senate resolution passed, I received a late-night phone call from Europe. A senior German finance ministry official wanted to inquire what on earth had just happened in Washington.

“Why did the Americans do this?” he inquired. “Who’s behind this?” From previous meetings, he knew that I had an interest in the sovereign debt issue and Eastern Europe’s economic and political transformation.

“But didn’t you tell me before the Germans would be in favor of it themselves?” I asked him.

“Well, yes, but we didn’t really mean it. After all, it will cost us a lot of money. We had banked on the longstanding U.S. position to be opposed to debt forgiveness for any nation, as they had practiced in Latin America.”

This admission left me perplexed, for several reasons. First, how smart is it for other major nations simply to hide behind the Americans when it comes to key policymaking issues?

Second, what about Germany doing for Poland what the United States had done for Germany earlier? A key dimension of the U.S.-led debt forgiveness move for Poland was to copy a move the U.S. government had made in 1953.

Back then, it had wisely chosen to reduce Germany’s old debts, in order to make sure the fledgling Federal Republic would not sink under the weight of the financial and economic legacy of the world wars.

Third, as Poland’s immediate neighbor, Germany should have a better, more strategic sense of what needed doing. Apparently not.

With all of this in mind, I rejoiced in answering his pressing question as to the “who did it.”

“Well, sir, as to who’s behind it, now that you tell me of your fine principles, I am willing to confess that I was the one asked to draft the U.S. Senate resolution.”

Not inclined to carry on the conversation, I followed my confession up with an immediate “Good night” — and hung up the call from that “principled” man.

When European borders disappear

The second historical footnote concerns the fact that I was a German citizen. In fact, I still am. Better yet, on my late father’s side, my family hails from Lower Silesia, the area around Wroclaw, which is now in Poland.

To me, doing the right thing for Poland meant doing the right thing for Europe — and, naturally, also for Germany’s well-understood interests. It was clear back then, and is much clearer now, that an economically stronger Poland means a better Europe. That’s what European integration, done correctly, is all about.

That it took the detour via the U.S. Senate — and the happenstance involvement of a German working in Washington — can be chalked up to one of the many ironies of history. Who cares — as long as it worked out in the end?

Poland 25 years after

Finally, the third historical footnote: On June 5, I will receive the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland from the President of the Republic of Poland, Bronislaw Komorowski, in Warsaw. The award is given “for outstanding services rendered to the promotion of Poland’s transition to democracy.”

The award is all the sweeter as the ceremony is part of the 25th anniversary celebrations of freedom in Poland.

I am only sorry that former U.S. Senator Bill Bradley, whose intervention caused me to become the drafter of the resolution, can’t be there himself. The former basketball pro and U.S. presidential candidate recently underwent a hip replacement operation.

Either way, both of us are very happy that our collaboration created the necessary financial maneuvering space for Poland to make a full success of its economic, social and political transformation.

Finally, I am also happy to report that, as is evident to anybody who has followed the eurozone crisis of recent years, the German and the Polish governments are now quite fully aligned.

In fact, there have been many incidences where the German and the Polish finance ministers ended up finishing each others’ sentences. And the rapport between Germany’s Chancellor and the Polish Prime Minister is excellent as well.

Both countries see eye to eye on many issues in their bilateral relations, something that cannot be said about Germany’s longstanding top partner in Europe, France.

Debt forgiveness for Poland was definitely worth the price — on very many levels.

Takeaways

What about Germany doing for Poland what the United States had done for Germany earlier?

In 1953, the US had reduced Germany's old debts so it would not sink under the financial legacy of the world wars.

Doing the right thing for Poland meant doing the right thing for Europe and for Germany's interests.

Clear back then and much clearer now, an economically stronger Poland means a better Europe.