Germany’s New Government: Abandoning German Interests in Europe

Don’t blame the French for seeking to pursue French interests and see to it that the French economic model prevails in Europe. But Berlin acts imprudently by accommodating that desire.

February 12, 2018

Since the end of World War II, politics in Europe has been about finding a balance between French and German interests.

Lessons from history

The French had drawn one key lesson from their experience with the Treaty of Versailles ending World War I in 1918: Europe could not be stabilized politically if other European countries ignored German interests.

The Germans, for their part, had learned from the crash of the Weimar Republic into National Socialism and the Third Reich that it was in their interest to embed Germany firmly in European structures. This created the basis for European cooperation after World War II.

A package deal

From the French perspective, the purpose of European integration was twofold: First, to improve the security of France by gaining political control over the German economic powerhouse and, second, to increase French political influence in both Europe and the world.

From the German perspective, European integration primarily served two purposes: First, to allow reconciliation with neighboring countries after two wars and, second, to promote economic growth by enlarging the markets for German industry.

European cooperation proved very advantageous for both countries, but that success was also always overshadowed by the difficulty to reconcile two opposing views on economic policy.

No twins

In France, the task of the state was seen to lead industry and manage the economy. In the system of “planification,” the state set specific targets that industry was supposed to pursue. In later stages, policymakers tried to keep the economy on course by managing aggregate demand with fiscal and monetary policy.

When the point was reached that fiscal policy ran out of steam (due to the accumulation of high government debt) and monetary policy reached its limits (because of the decay of the currency), the introduction of a European currency was supposed to provide proper remedy for France.

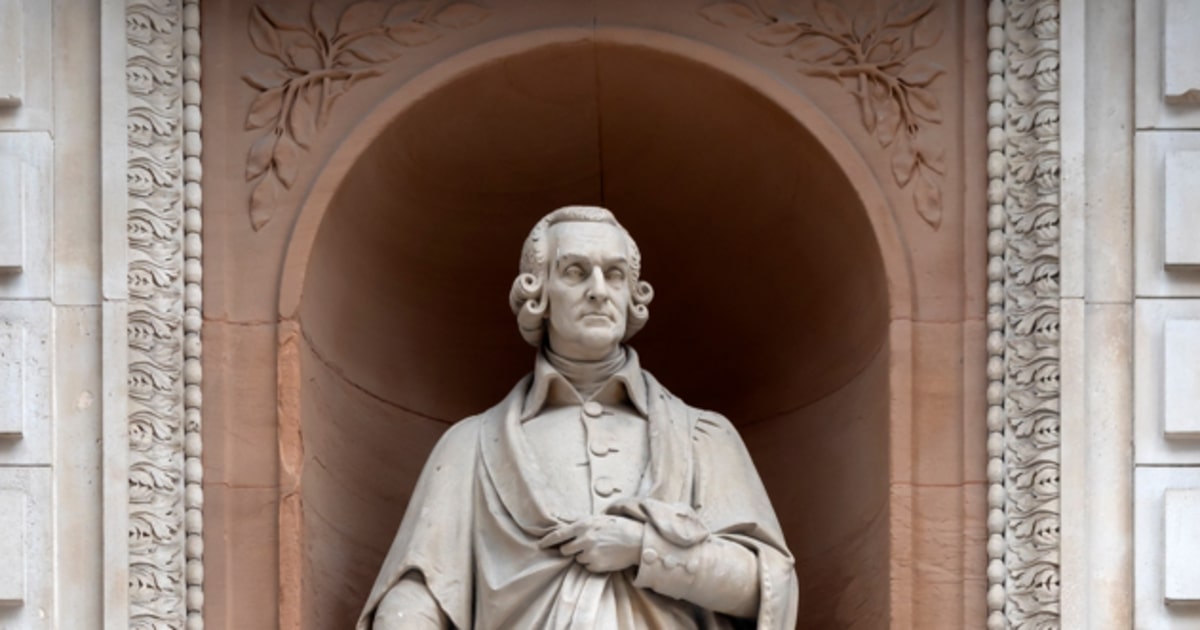

In Germany, by contrast, successful currency reform and economic liberalization introduced by the legendary economics minister Ludwig Erhard after WWII gave German economic policy and the German market a liberal bent.

The “Erhard generation” of senior officials did not think much of industrial policy and was skeptical about Keynesian demand management. They countered French state-oriented policies with distinctly market-oriented ideas.

Two different sets of economic DNA

This difference in views has created conflicts that have affected all European projects. These became ever more difficult to reconcile the closer European integration became.

Most importantly, European Monetary Union was based on many shady compromises. These have made the European single currency very vulnerable to financial tensions. It almost broke apart in 2012 and, for all the soothsaying, is still not yet on safe ground today.

Berlin taking France’s bait

However, it seems that the emerging new German “grand coalition” government is willing to resolve the underlying conflicts. It seems prepared to give up Germany’s interest in the pursuit of a market-liberal approach in the field of economic policy in favor of France’s preference for state dirigisme.

To that end, the new German government supports:

• the regulation of minimum wages and minimum welfare across the European Union;

• a common base and minimum rates for corporate taxes;

• a European Monetary Fund (EMF), set up as an institution of the EU – and hence at considerable distance from the German parliament, to succeed the European Stability Mechanism;

• new financial facilities for demand management policy and investment at the EMF; and

• larger German contributions to the EU budget.

In addition, Peter Altmaier, the acting finance minister and the country’s designated new economics minister, has signaled German agreement to a common deposit insurance scheme for the entire euro area. That project had been firmly resisted by his predecessor Wolfgang Schäuble.

The intended policy course of the emerging new German government boils down to abandoning long defended German interests in market-liberal economic policies, sound finances and a hard currency.

Financial responsibilities are to be mutualized, investment will be politically directed and the economy regulated by the state. German tax payers are to pay more into the EU budget, although Germany is already the biggest net contributor. German bank customers are supposed to co-finance deposit insurance in states with weaker banking systems.

Subordinating German under French interests

Berlin’s new approach to European policymaking is supposed to foster European harmony by subordinating German under French interests. However, it is much more likely to deepen European frictions.

It is hard to imagine that any other EMU member state will follow the German example, abandoning its own national interests, as is the intention of the German government.

Consequently, the new German policy will be welcomed by the states of Southern Europe who benefit from it. And it will be fought by other states whose interests are opposed by those outside Europe’s South.

Governments in countries such as Austria, Netherlands or Slovakia are hardly likely to subjugate their interests to the demands for more redistribution and state dirigisme of the Latin-influenced European group of countries led by France.

Germany: Doubling down on the Brexit fallout

It is especially disturbing that Germany abandons its previous interests at a time when the UK is preparing for exiting the EU. It is worth recalling that it was Germany that in the early 1970s supported EU entry of the UK.

The German government was keen to win a market-liberal partner in the Brussels club.

Unsurprisingly, France had blocked UK entry for many years because it feared the liberal British influence. And it was Germany which insisted on key rules for European Monetary Union. The most important of them was to hold every member responsible for its own finances in order to preserve financial discipline.

In contrast, France saw in a single European currency primarily as an instrument for a laxer economic policy. Against German interests, the euro was transformed during the euro crisis to a politically useable instrument for the funding of cash-strapped EMU member states.

While that was bad enough an outcome for Germany, with Brexit Germany will also lose its most important market-liberal partner on the inside of the EU.

Don’t blame the French!

It is not only legitimate, but also the duty of French President Emmanuel Macron to pursue French interests and see to it that the French economic model prevails in Europe.

What is to be deplored is that the German government is evidently abandoning the formulation and pursuit of German interests. That is not only politically stupid, but will actually also deepen the crisis of the European Union.

Especially in the face of Brexit, the logical goal of German policymaking in Europe should be to counter French central planning with Germany’s well-proven, market-liberal policies in the tradition of Ludwig Erhard.

To keep Europe prosperous and united, competition in the Single Market needs to be strengthened and the operations of the ECB refocused on the provision of sound money.

To those ends, the German government should, among other things, insist on:

• the ending of monetary funding of government debt by the ECB;

• a reform of voting rights in the ECB Council according to the economic weight of a country;

• a change from the present activist to a long-term monetary policy aimed at maintaining the purchasing power of money;

• the limitation and stricter control of financial assistance by the European Stability Mechanism (or a European Monetary Fund as its successor);

• the possibility for debt restructuring and exit of over-indebted and uncompetitive member countries of EMU;

• the effective protection of the borders of the Schengen area;

• the harmonization of asylum law and immigration rules in the Schengen area;

• the prevention of unauthorized immigration into welfare systems;

• a reduction of barriers to trade in the single market;

• an increase in the effectiveness of the countless EU financial assistance facilities; and

• the refocusing of the EU budget on projects for the future instead of subsidies for agriculture.

The German government should reserve the option to withdraw from community projects when vital German interests are violated. For instance, the Bundesbank should withdraw from the interbank payment system Target 2, if future balances are not settled by asset transfers, the ECB continued to monetize government debt, and voting rights in the ECB Council were not changed.

Conclusion

To avoid any misunderstanding: The purpose of a clear articulation and pursuit of German interests is not to provoke other countries.

Existing conflicts of interest can only be settled when they are clearly formulated and put against the interests of others. If this is not done, suppression of one’s own interests will create resentments that could eventually lead to the complete withdrawal from common European causes.

Europe has always benefited from the recognition of opposing interests of France and Germany, of course including the search for reconciliation of those differences, where possible. It will suffer when Germany ceases to purse its own interests for the benefit of France.

Takeaways

Don't blame the French for seeking to pursue French interests and see to it that the French economic model prevails in Europe. But Berlin acts imprudently by accommodating that desire.

Berlin’s new approach to European policymaking is supposed to foster European harmony by subordinating German under French interests. However, it is much more likely to deepen European frictions.

It is hard to imagine that any other EMU member state will follow the German example and abandon its own national interests as is the intention of the German government.

The new German policy will be welcomed by the states of Southern Europe who benefit from it. And it will be fought by other states whose interests are opposed by those outside Europe’s South.