High Time for a Western Oil Strategy

Yes, we can boost global security and good governance.

January 26, 2016

Over the last 18 months, the oil price has fallen from around $110 per barrel to around $30. The oil price collapse creates new uncertainties, including greater rivalries in the Middle East, more internal turmoil in Venezuela and a strain on Vladimir Putin’s grip on power.

But the price collapse also offers geopolitical opportunities. A post-OPEC world is emerging.

It is essential that Western countries lose no time in seeking to forge a new international oil strategy and shape a more secure future – secure from a military perspective and also from a humanitarian one.

Over the past four decades, the rulers of most OPEC countries became very rich, built modern armies and captured all the levers of governance.

In sharp contrast, a majority of the citizens in most of these countries enjoyed none of the benefits. Indeed, in many of these OPEC-member countries, poverty and corruption both rose.

Oil as a war trigger

At present, demand for oil is very low relative to the abundant supply. This situation is not likely to change soon.

This is, therefore, an ideal time for Western governments to put in place a strategy to ensure that oil will no longer be a crucial factor in launching wars – as it has repeatedly been in recent decades.

Using Freedom House’s annual index as a guide, a veritable alphabet of some 28 natural resource-exporting nations, from Angola to Zimbabwe, are categorized as “not free.” This underscores that much of the world’s oil comes from countries run by corrupt and repressive regimes.

To understand the exceptional opportunity that today’s changing global oil dynamic offers, it is worth taking a close look at a weighty new book: “Blood Oil – Tyrants, Violence and the Rules that Run the World,” published by Oxford University Press.

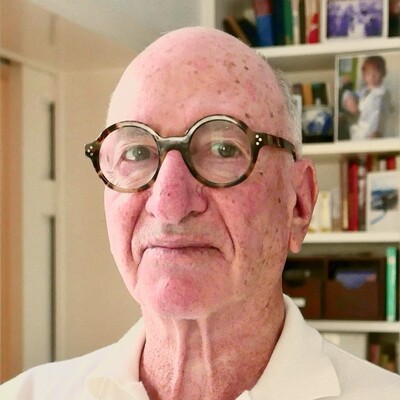

Professor Leif Wenar, chair of philosophy and law at Kings College, London, takes us on a journey around the world of oil dictatorships.

The main thrust of his book is the proposal that the West should adopt a “Clean Trade Act.” It would gradually see the end of Western purchases of natural resources from authoritarian resource-exporting regimes.

Such Western pressure is key to convince these governments to be more accountable to their own citizens. Such efforts, according to Professor Wenar, will enhance our security.

A “Clean Trade Act” is a catchy title for what amounts to a regime of trade boycotts and sanctions on corrupt foreign governments. This is admittedly fraught with risks.

Sanctions not helpful

The increasing clashes between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and their proxies, could well become more explosive if Western countries added pressure on both of them to become more democratic and explicitly threatened to curb oil purchases.

Further sanctions on Putin and his cronies might lead Russia’s leader to even more dangerous overseas adventures.

There are some obvious counter-arguments. One is what good would sanctioning the authoritarian resource governments do if China and other Asian countries did not participate?

Blood Oil’s author suggests that they will join “the Clean Trade Act” in time because they will not want to become increasingly reliant on their natural resources or on unstable and unpredictable resource-exporting governments.

He also believes international institutions such as the World Trade Organization and multinational corporations will support his approach.

Quick reality check

I am skeptical if this can work. For example, there is very little evidence from years of discussions within the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) that the major oil companies would ever contemplate withdrawing from a country irrespective of how vicious and corrupt that country’s government.

Of course, it is intolerable that we preach the values of freedom and democracy and human rights, yet we trade with and buy oil from governments who trample on such values.

Even so, much as we would wish otherwise, trade boycotts and sanctions are not likely to be the productive path to reform in an area as complex as global oil.

Anti-corruption and human rights organizations for the most part have notably not been at the forefront of calls for trade sanctions against governments.

They have sought to avoid becoming part of the toxic politics of “the West against the rest.”

Grass root movements

A preferable approach is to proceed on a country-by-country basis, striving in each case to build grass roots citizens movements for accountable and transparent governments and for systems of justice that end the impunity of government leaders and their cronies.

Such approaches need to be augmented by enforcement of existing global agreements against corruption (such as the United Nations Convention Against Corruption) and money laundering (such as recent Group of 20 decisions and actions by the Financial Action Task Force).

The merit of Wenar’s contributions rests in his timing. Now is absolutely the right moment for Western governments to take stock of their relationships with authoritarian resource- exporting regimes.

They ought to come up with a strategy that leads to a world made more secure as governments that control oil become more accountable to their own citizens.

Takeaways

An oil price collapse offers geopolitical opportunities. A post-OPEC world is emerging.

The West should adopt an act to end purchases of natural resources from authoritarian regimes.

Trade boycotts and sanctions are not the productive path to reform in global oil markets.

“Clean Trade Act” is a catchy title for a regime of trade sanctions on corrupt foreign governments.