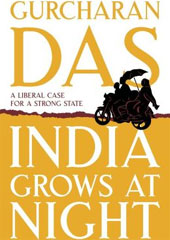

India Grows at Night

How could a nation become the world’s second-fastest growing economy despite having a weak, flailing state?

January 11, 2013

When two Indians sit down to sip chai, they quickly agree that their country seems to be on the rise, despite the actions (or inactions) of the government. Poetically, but realistically, they capture the idea of private success and public failure as “India grows at night, while the government sleeps.”

But how could a nation become the world’s second fastest growing economy despite a weak, flailing state?

My big question for my country’s future is this: Shouldn’t India also grow during the day? The recent economic slowdown is a sign that India may have begun to experience the limits of growing at night.

The economic rise of India has been the defining event of my life. It is not only good news for its 1.2 billion people, but is also an instrument for good in the world.

At a time when Western economies and their way of doing business are under a cloud, a large nation in the East is rising based on political and economic liberty.

It proves, in an entirely different world region, that open societies, free trade and multiplying connections to the global economy are pathways to lasting prosperity and national success.

India has finally joined the great human adventure that began 200 years ago on an island in northwest Europe, which brought about an amazing rise in the standard of living of the human race. Until the industrial revolution, for 70,000 years or 99% of human history, the vast majority of humanity lived lives that were mostly “poor, nasty, brutish and short.”

Twenty-five years of high growth have made India one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. Although it has slowed recently from a scorching 9% rate prior to the global financial crisis, India is likely to continue to grow at between 7% and 8% for the next couple of decades.

This means that a large majority of Indians will soon emerge from a struggle against want into an age when they will be at ease. Like many parts of Asia, India, too, will turn into a middle-class nation.

This will not happen uniformly. Gujarat will be ahead of Bihar, but even Bihar will catch up. Poverty will not vanish, but the number of poor will come down to a manageable level, and importantly, the politics of the country will also change.

A baffling story

Indians are baffled by the rise of their country. And for good reason. Consider this tale of two towns on the outskirts of Delhi — Gurgaon and Faridabad.

In 1980, Faridabad had an active municipality, fertile agriculture, a direct railway line to Delhi, a host of well-known industries and state government determined to showcase it as the state of Haryana’s future.

Gurgaon, located in the same state, was at the time a sleepy village with rocky soil and pitiable agriculture. It had no local government, no railway link and no industry. Compared to pampered Faridabad, it was wilderness.

Twenty-five years later, Gurgaon had become the symbol of a rising India and an engine of international growth. It now has dozens of shiny skyscrapers, 26 shopping malls, seven golf courses and countless luxury showrooms of global brands.

It has 32 million square feet of commercial space and hosts the Indian offices of some of the world’s largest corporations. Its economy is reflected in fabled apartment complexes with swimming pools, spas and saunas, which vie with the best gated communities anywhere.

Meanwhile, Faridabad remained sad and scraggly. It is groaning under a corrupt, self-important municipality. How did this happen?

Gurgaon’s erstwhile disadvantage — that it was more or less ignored by the rapacious state government — turned out to be an advantage. It meant less red tape and fewer bureaucrats who could block its development.

Gurgaon flourished primarily because of its self-reliant citizens, who did not sit around and wait for the government. They dug wells to get water. They put in diesel generators to make up for the state electricity board’s failure.

They also employed security guards — rather than depend on the police. They used cell phones — instead of landlines of the state-run telephone company. And they used couriers rather than the post office. Some buildings even installed sewage treatment plants.

Since teachers and doctors, although on the state’s payroll, did not show up at government schools and health centers, the citizens opened cheap private schools and clinics. Crucially, they even did so in the slums, where fees were as low as Rs 200 ($4) per month.

Modern India is in some ways Gurgaon writ large. When Indians witnessed the stupendous rise of the IT industry and of cities like Gurgaon, they began to ask, “Why do we need a government at all, with corrupt politicians and unresponsive bureaucrats?”

And they came to say mockingly, “India grows at night when the government sleeps.”

To rise without the state is a brave thing. But is it wise or sustainable? Gurgaon would clearly be better off with a functioning public drainage system, reliable water and electricity, good schools, roads and parks, as well as a decent public transportation system.

Ultimately, Faridabad and Gurgaon are both the wrong models of governance for India’s future. If red tape and corruption are the downside of Faridabad’s model, the problem with Gurgaon’s laissez-faire model is the lack of basic services.

While India’s economic rise is a good thing and necessary for lifting the poor, it is not sufficient. We also need honest policemen, diligent officials, functioning schools and primary health centers. In short, India needs a strong liberal-minded state.

What is a strong liberal state?

A successful liberal democracy has three elements, as Francis Fukuyama explains in his book, The Origins of Political Order. It has strong authority to allow quick and decisive action, a transparent rule of law to ensure the action is legitimate, and it is accountable to the people.

This was the original conception of the state as imagined by the classical liberal thinkers. They inspired both America’s and India’s founding fathers.

In America’s case, it is clear for all to see now that combining these three elements is not easy, as they tend to check each other. But in India, we seem to have forgotten that the state was created to decide and act. It should not take eight years to build a road when it takes three elsewhere. It should not take ten years to get justice instead of two.

The rule of law in India has weakened as a result of populist and patronage politics, unaccountable officials, judicial delay and a toady police. There is widespread paralysis in executive decision making.

Parliaments, not just at the union level, but also at the state level, are too often weighed down by gridlock. The courts routinely find themselves in a position where they dictate action to the executive. An aggressive civil society and media have enhanced accountability in India, but it has also enfeebled the executive.

As a general rule, leftists tend to desire a large state, while rightists want a small one. Neither is the correct formula for India. What India needs is a strong, efficient and enabling state with a robust rule of law and accountability.

A strong liberal state is efficient in the sense that it enforces fairly and forcefully the rule of law. It is strong because it has independent regulators who are tough on corruption and ensure that no one is above the law.

A strong liberal state is enabling because it delivers services honestly to all citizens. It is definitely not a benign dictatorship, which is how I see Singapore, with its enviably high level of governance but its absence of true democratic liberties.

Neither is it intrusive like the license raj. It is a rules-based order with a light, invisible touch over citizens’ lives. Just how that kind of order should look is what I cover in the next feature in The Globalist, India: Confessions of a Disillusioned Libertarian.

Editor’s note: This essay is adapted from India Grows at Night: A Liberal Case for a Strong State (Penguin) by Gurcharan Das. Published by arrangement with the author. Copyright © 2012 by Gurcharan Das.

Takeaways

Indians ask, "Why do we need a government at all, with corrupt politicians and unresponsive bureaucrats?"

While India's economic rise is a good thing and necessary for lifting the poor, it is not sufficient.

A strong liberal state has independent regulators who are tough on corruption.

In India, we seem to have forgotten that the state was created to decide and act.

Read previous

Ranking U.S. Economic Growth

January 10, 2013