Iraq: Is It All the American Indians’ Fault?

What effects have America’s 19th-century Indian wars had on “civilizing” efforts in Iraq?

December 19, 2007

WMDs. Oil. Cheney. Neoconservatives. The media. Rumsfeld. Iraqi dissidents. Faulty intelligence. Forget it all. To get a real handle on why the nation slipped into the long war, go no further than American Indians.

“Go West, Young Man!”

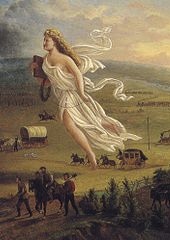

Long before the journalist John L. O’Sullivan developed the idea of Manifest Destiny in 1845, Americans had been fighting, displacing and killing American Indians.

As the country expanded its territory westward — into what were considered uninhabited “free” territories that led to the natural barrier presented by the Pacific Ocean — American expansionists declared that there was a duty to spread their culture and political institutions among the “savages.”

Tempting ideas and beliefs

Armed with the right to conquer and clear the land that had for centuries been inhabited, the United States faced little genuine resistance, and the ruthless expansion killed great numbers of Indians.

With the Iraq adventure now on the brain, we must ask: Is it possible that the success of westward expansion produced a natural disposition toward external conquest — and, worse, the tempting belief that such civilizing missions were easily accomplished?

One has to wonder whether the collective American mind began to imagine that all further attempts at foreign conquest would be as fruitful as the original.

Justifying war

The period before the United States’ first major move as an imperial nation — the 1898 Spanish-American War — saw the growth of the propagandist “yellow press” of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer. Many Americans were supremely confident of success in the war — though the country had not fought another European power since the War of 1812.

Future U.S. President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the Navy, was one of the biggest agitators for the war.

Roosevelt and the Indians

Roosevelt had achieved recognition as a serious historian of the time, and in the years preceding the war with Spain, he published The Winning of the West, a four-volume history of the frontier and defense of the fight against the American Indians.

“It was all-important that it should be won, for the benefit of civilization and in the interests of mankind,” he wrote. “It is indeed a warped, perverse and silly morality which would forbid a course of conquest that has turned whole continents into the sears of mighty and flourishing civilized nations.”

The man now primarily known — and cherished — as the first champion of the U.S. national parks, Roosevelt argued further that “the conquest and settlement by the whites of the Indian lands was necessary to the greatness of the race and to the well-being of civilized mankind.”

Teddy Roosevelt, Blow by Blow:

Any doubters may want to explore whether there is a strangely familiar — and contemporary — ring to Roosevelt’s rather bellicose language:

For example, does the following provide a reference to the war against Indians, or today's War on Terror:

“The most ultimately righteous of all wars is a war with savages, though it is apt to be also the most terrible and inhuman.”

And what about this statement:

“The very causes which render this struggle between savagery and the rough front rank of civilization so vast and elemental in its consequence to the future of the world, also tend to render it in certain ways peculiarly revolting and barbarous.

“It is primeval warfare, and it is waged as war was waged in the ages of bronze and of iron. All the merciful humanity that even war has gained during the last two thousand years is lost. It is a warfare where no pity is shown to non-combatants, where the weak are harried without ruth, and the vanquished maltreated with merciless ferocity.”

Teddy Roosevelt in 1896 or President George W. Bush in 2006:

“America did not ask for this war, and every American wishes it were over. So do I. But the war is not over — and it will not be over until either we or the extremists emerge victorious. We are in a war that will set the course for this new century — and determine the destiny of millions across the world.”

But back to "Teddy" Roosevelt. He further opines:

“It is as idle to apply to savages the rules of international morality which obtain between stable and cultured communities.”

And when he goes on to say…

“No treaties, whether between civilized nations or not, can ever be regarded as binding in perpetuity. With changing conditions, circumstances may arise which render it not only expedient, but imperative and honorable, to abrogate them.”

…who doesn't hear the sound of Donald Rumsfeld's voice?

And Roosevelt…

“No treaty served the needs of humanity and civilization, unless it gave the land to the Americans as unreservedly as any successful war.”

…could serve as eloquent a statement from congenital UN hater — and former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations — John Bolten.

The kindness of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq?

“No other conquering and colonizing nation has ever treated the original savage owners of the soil with such generosity as has the United States.”

On the men and women of the U.S. Army:

“The hard, energetic, practical men who do the rough pioneer work of civilization in barbarous lands, are not prone to false sentimentality. The people who are, are the people who stay at home. Often these stay-at-homes are too selfish and indolent, too lacking in imagination, to understand the race-importance of the work which is done by their pioneer brethren in wild and distant lands; and they judge them by standards which would only be applicable to quarrels in their own townships and parishes.”

On the U.S. Army — or the new Iraqi government?

“It is the men actually on the borders of the longed-for ground, the men actually in contact with the savages, who in the end shape their own destinies.”

Case closed.

Read previous

The Globalist’s Best Books of 2007

December 17, 2007