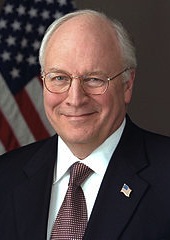

Redeeming Cheney

How can Vice President Dick Cheney salvage his historical legacy?

May 9, 2007

An entire cottage industry has emerged recently in Washington to speculate about the legacy of the vice president.

Suggestions range from the unoriginal (the man who needed no case for a war in Iraq because he thought it was self-justifying and needed no plan for it because he thought it would be self-executing) to the subversive (the man who put teeth in conservative paranoia by making it self-fulfilling).

While unenlightening in itself, all this talk about Mr. Cheney's legacy has provoked real creativity from his defenders. Just in case history fails to see matters clearly, they reason, it's prudent to burnish the vice president's legacy while he's still in office.

The plan for Mr. Cheney is surprising but potent — to lend the full weight and support of the Office of the Vice President to the "Arc," Rand Corporation's formal structure for a viable Palestinian state.

The brainchild of visionary urban designer Doug Suisman and his multidisciplinary team of Rand analysts, the Arc lays out the architecture for a Palestinian city-state that could thrive. It is nothing less than a mesmerizing view of the possible for a place that has forgotten hope.

A simple map tells it all. Palestine is not so much a country as a metropolitan area about the size of the San Francisco Bay Area. So the Arc is a subway line that starts under Gaza City on the northern border of the Gaza Strip. It heads south under Deir al Balah, Khan Yunis, and a new stop — Airport.

It then travels under Israel's Negev Desert to the southern end of the West Bank, stopping just east of Hebron, Bethlehem and Jerusalem, and at a joint station between Ramallah and Jericho.

The Arc continues along the parched and barren spine of hills east of the West Bank's main cities, stopping near Salfit, Nablus, Tubas — and finally Jenin.

The design exploits nearly uninhabitable conditions on the desiccated crest of the West Bank's hills that have left a clear path for construction. An up-to-the-minute water and power distribution system would run above the subway along an end-to-end greenway functioning as a sort of West Bank Central Park.

Better still, cross streets would run from each subway station to its corresponding old city center, providing perfect frontage for new neighborhoods already stitched into the transportation and utility grid without over-crowding existing towns.

The economic impact would be transformative. A young man in the dusty streets of the Gaza Strip's Khan Yunis could get to a job in the West Bank's busy Ramallah within half an hour without setting foot on Israeli territory.

That beats hanging out at the local café hoping for construction work and listening to various dead-enders spin dreams of jihad as they smoke.

The most extraordinary feature of the plan, however, has already had a practical effect. With its curling subway spine and ladder of connecting roads, the Arc unifies Palestine from the center. The hundreds of encroaching Israeli settlements around the western periphery of the West Bank have virtually no impact on its feasibility.

When Suisman's team presented the Arc to Palestinian President Abbas' cabinet, several members wept. But the real news was that Israeli settlement activity in the West Bank started to decline.

Of course, settlements, many on disputed land, are still economically attractive to the settlers. But the very existence of a way to knit together a Palestinian city-state that settlements cannot block means they no longer represent what a long line of Israeli prime ministers have called "facts on the ground."

Nobody at Rand expects Palestine to implement any part of the Arc while it's at war. But it shows that the state could be fully viable if it were at peace. Rand estimates that the core elements of rail and road infrastructure would cost about $6 billion, employing 100,000 to 150,000 Palestinians over a five-year period.

According to the Iraq cost clock in New York City's Times Square, it takes the United States just under 34 days to spend $6 billion in Iraq. Of course, Arab oil states would be so anxious to rebuild Palestine that it is doubtful they would leave anything for the U.S. government to fund — even if it wanted to contribute.

While intended merely as a vision of hope, only three things stand in the way of building the Arc right away. First, it requires peace. Second, it requires a nod from the United States. And third, it requires a competent general contractor.

Vice President Cheney is the one man on the planet who could deliver all three tomorrow.

He certainly has the bona fides to win a cessation of hostilities that would allow planning and construction to begin. And the prospect of jobs absorbing young Palestinians would quickly garner Israeli support. In fact, one Likud Member of Parliament, hearing a briefing on the idea, asked simply: "Where's Israel's Arc?"

Finally, after its extensive experience over three decades and two wars in Iraq, there can be no doubt that Halliburton — the company formerly led by Mr. Cheney — is up to the task. It's the least the vice president could do for the company he used to run to honor the employees it has lost to the second Iraq War.

The calculation that implementation of the Arc could redeem Mr. Cheney's legacy looks sound. By transforming Palestine into a well-connected metropolitan area, the Arc could release the entrepreneurial energy that had begun to stir in Ramallah in the late 1990s when people were thinking of business rather than intifida.

The reason is that modern economies need networks above all else. But networks are out of reach for Palestinians today. A quick look at a map of the West Bank shows terrain that looks like Swiss cheese, pock-marked by hundreds of Israeli settlements — many on contested land. Neighbors cannot communicate, cannot transact and cannot cooperate in simple businesses.

The Arc would change all that in a hurry. And nothing holds out the prospect of marginalizing Palestine's dead-end jihadists like entrepreneurial alternatives that would let young men support families for the first time in years.

A Palestine that settled down to business would be a natural partner for the Israel that has instead had to endure the bombs of its enraged militants. And an enduring basis of peace between Palestine and Israel changes much else for the United States.

Perhaps the most important thing that it changes is the simple belief, now universal in the Muslim world, that Americans view Islamic men and women as less than the other men and women of the world. It's beguiling to think that complex dreams of a revived Caliphate motivate today's Islamic terrorists.

But why reach for such mysterious explanations when the widespread belief that Americans hold Muslims in contempt is more than sufficient to explain the dynamics of Islamist politics today?

The vice president's creative backers are betting that his support for the Arc would reverse that damaging belief — and ensure the legacy he thought he had secured when Saddam's statue tumbled down.

Read previous

Global Governance and the Division of Labor

May 8, 2007