Shooting Chechnya

How did Stanley Greene end up photographing war in Chechnya?

July 21, 2004

In November 1989, I went to Berlin for amusement — and found myself stranded on the East side. There was a massive demonstration and the Stasi (East German secret police) came out ready to shoot at the crowd.

The demonstrators marched to the wall and I followed. I was caught in a moment of history. I had never felt anything like the adrenalin that rushed through me that day. Something was happening and I was part of it.

I saw a girl standing on top of the wall wearing a green tutu, a leather jacket and a Stasi cap, holding a bottle of champagne. I snapped a picture and a moment later she was gone. That photograph went round the world.

Later, back in Paris, I took off with a friend to Mauritania. I knew nothing about photographing war or how to photograph a mother with her dying baby in her arms. I separated from my friend, got on the wrong bus and found myself amid Touareg tribesmen.

They insisted I follow them to where thousands of their people had taken refuge on the Mauritania border after being expelled from Mali. They told me to take photographs, but at first I couldn't. I had never seen dying people with flies in their faces.

So I photographed them as I would photograph a fashion model. That work was later screened at the Visa pour l'Image international photo festival at Perpignan. I dislike those pictures — they have no soul. But they taught me a lesson: You have to take photographs from the heart and not from the head.

Having seen my book "Somnambule," (Sleepwalker) about creatures of the night, Christian Caujolle encouraged me to become a member of VU photo agency. I joined in 1991.

During the Somalia war in 1993, I chose to go to Southern Sudan where there was a terrible humanitarian crisis. This time, I wanted to photograph with my vision.

This is photography that is on the edge of failure — because there is no thought about technique, no set-ups. This is about getting as close as possible, capturing life and death, not backing off. I lived in the camps for three months. People died in

front of the camera.

That year, I took my first trip to the Caucasus, to another war, in Nagorno Karabakh, then on to Croatia. I went to work with the mujahideen in Kashmir and then to revisit the Bophal Union Carbide disaster.

This led on to the civil war in Georgia and a trip around the Caspian. I first went to Grozny in February 1994 for the French Daily Liberation, before the hell of Rwanda in August 1994. By January 1995, I was back in Chechnya.

At first, war photography seemed like a way to test myself, to exist on a knife-edge where there is constant proof of being alive. Today, covering conflicts is simply a very personal form of protest.

Having witnessed many wars, I can honestly say that the evil of the Chechnya situation bears few comparisons.

The starting point of a decade of work in Russia was the day of the putsch spearheaded by Boris Yeltsin in October 1993. At the time of the insurrection, I was the only foreigner inside the parliamentary building.

It was a baptism of fire. Tanks fired at the building and suddenly I was covered in rubble and shattered glass. I continued to take pictures and I thought I would just go on until I died — as 1,000 others in the building did.

I walked down from the wreckage of the 17th floor. I went on to Abkhaziya, where Shamil Basayev — with his special Spetznaz forces — was fighting the Georgians. I soon heard rumours that war in Chechnya was imminent.

When I first arrived in Grozny in February 1994, everyone I saw had a machine gun or some kind of weapon. I was fascinated by their fierce display of independence.

Chechnya got its hooks into me. I tried to cover the war from the Russian side, but all that my sight was offered was propaganda.

Until October 1999, access to Chechnya was relatively easy, but became closed or strictly controlled. Journalists who wanted to investigate what was going on had to sneak in down the muddy back roads aboard bullet-ridden vehicles and do their job clandestinely.

There is nothing open about what is happening in Chechnya. The only thing that is open is the wound that continues to bleed.

In Chechnya fear sticks to you like your shadow. The sound, smell and reality of death follow you everywhere you go.

The Russian military have some 400 checkpoints throughout the territory, 100 of them in Grozny, manned by poorly trained, trigger-happy soldiers who exact bribes. Streets are booby-trapped and buildings are strung with trip-wire.

Death happens without warning. There is no such thing as taking photographs from a place of safety. I started to perfect what is known as "the hundred-yard stare." I was clandestine, gathering information in secret — stealing images with my Leica.

Journalists become attached to conflicts and their revolt against injustice colors their writing, their photographs and their films. At a certain point, some have to get off the fence.

We are not disaster tourists. When we see atrocities being committed under our eyes, we have to fight back. I use my cameras as weapons and try to portray the human story in this dirty war. Photographs should be beyond politics.

I cannot list all the times someone protected me, took me in to share their last bit of food, gave me a place to sleep, saved my life. Over the years, the Chechen war also became my story.

Back in the world, it is hard to sit with a group of friends and have a beer or a meal and know that the people you have just left are being arrested, tortured, raped or worse.

It is almost impossible not to play the role of the provocateur and difficult to imagine why others are not as angry as I am, while they in turn feel shut out from a world they have not experienced — and cannot imagine.

My photographs of this conflict are not about technique or 'art.' They are the product of pure gut feeling.

Although this collection of images casts a depressingly small light on the magnitude of sorrow associated with the conflicts, of the pointless rivers of blood shed by Chechens, my anger is total.

Reproduced from “Open Wound” by Stanley Greene. Copyright 2004 by Agence VU. Used with permission of the publisher Agence VU.

Author

The Globalist

Read previous

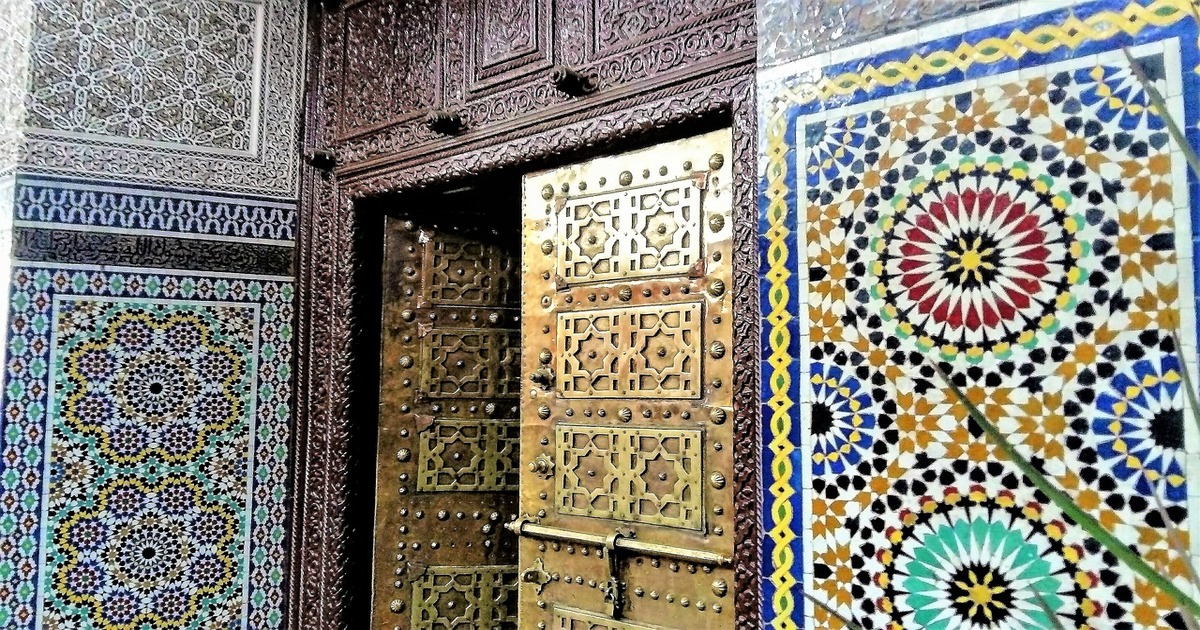

A Tourist in Morocco

July 19, 2004