TPP: Beware of the Japan Hype

Just as is the case in the US, there is very strong domestic opposition to TPP in Japan.

April 29, 2015

With Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in Washington, expectations are high that the U.S.-Japan bilateral relationship will be significantly strengthened.

His agenda includes:

1. Committing Japan to the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP).

2. Saying the appropriate penitent things in respect to the 70th anniversary of the war.

3. Enabling Japan to a greater role in regional and global security.

Given that Tokyo is now more in the mood of saying “yes” to Washington than saying “no,” it would seem likely that two of the three objectives may be met. Tokyo will find a formula for expressing its remorse over the war that will satisfy Washington, even if it does not satisfy Beijing and Seoul.

Furthermore, Tokyo should also commit to playing an enhanced security role in the Asia Pacific, especially if Abe’s goal to see Article 9 of the Constitution revised is realized. TPP is by far the thorniest issue – and the one on which it is key to preserve a realistic mindset.

Strengthening U.S.-Japan relations

No doubt, the Abe government is keen to conclude TPP as a means of bolstering the relationship with Washington. At the moment apart from Japan, Asian members of TPP are relatively minor: Brunei, Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam. China is excluded.

Thus, TPP is in essence a bilateral agreement that could consolidate the Tokyo-Washington Asia Pacific axis. But will it – or can it?

Trouble at home

It is important to know that, just as there is strong opposition to TPP in the United States – and it is by no means certain that President Obama will obtain Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) – there is also very strong domestic opposition to TPP in Japan.

The Japanese domestic economic deal that has endured over the decades since the end of World War II is based on a two-step approach.

On the one hand, certain key industrial sectors (electronics, automotive, office equipment, etc.) are promoted and internationalized, essentially through exports. On the other hand, weaker sectors (agriculture, pharma, distribution, services) are heavily protected, through quotas, tariffs and non-tariff measures.

Japan’s dual economy

This resulted in the so-called dual economy of Japan: an aggressive strong outward-looking export sector versus a defensive weak inward-looking highly protected sector. The latter acted, among other things, as a means of protecting jobs.

Japan enjoyed a long period of very low unemployment. The price that was paid for that is that Japan is effectively a closed economy. As John West of the Asian Century Institute has recently written, “The closed nature of Japan’s market is evident from its global ranking of 194th out of 198 countries for the stock of inward foreign investment and 167th out of 172 countries for imports (both as a share of GDP).”

This does not bode well for U.S. business and commercial interests. To be sure, a true opening up of the Japanese economy would not just be an important dynamic of Abenomics, the prime minister’s reform program. It would also be a positive force for the world economy.

However, Abe’s actual ability to deliver on a deal is very much in doubt, especially given the often vehement domestic opposition and fierce protests. The main thrust has come from the most potentially affected sectors, especially agriculture, fisheries and distribution, but also from two other sources: nationalists and democrats.

The nationalists argue that TPP will make Japan a colony of the United States. The democrats, like their counterparts in the United States and elsewhere, argue that the secretive nature of the TPP talks make them inherently anti-democratic.

Given that the country’s economy has stagnated over these last “lost decades,” the odds for fierce resistance to any deal with the United States are high. All the more so as a key plank of Prime Minister Abe is a rather unrestrained nationalism. Even at a time when the country fears China, Japanese pride is still wounded when it looks at America.

An uncertain future

It does not help Abe’s cause that Japan’s economic prospects are indeed gloomy. The economy is lacking in dynamism while society is aging. The population peaked at 127 million in 2010. Since then, it has been decreasing and, according to current demographic trends, will dip below 100 million in the course of the next 50 years.

As the heads of the world’s second and third biggest global economy and the major allies of the Pacific meet in a period of transformative turbulent confusion, expectations could justifiably be high that Prime Minister Abe’s visit will be a historical landmark.

Looking at Japan’s negative dynamics as well as the experiences of the very tangled U.S.-Japan relationship, it seems unlikely that, the leaders’ likely lofty rhetoric notwithstanding, there will be a new beginning.

The foundations of the relationship were too weak and perhaps especially too artificial to allow for a solid edifice to emerge. Expectations should be recalibrated.

Takeaways

Just as is the case in the US, there is very strong domestic opposition to TPP in Japan.

Japanese nationalists argue that TPP will make Japan a colony of the United States.

Even at a time when the country fears China, Japanese pride is still wounded when it looks at America.

Abe’s actual ability to deliver on a deal is very much in doubt.

Read previous

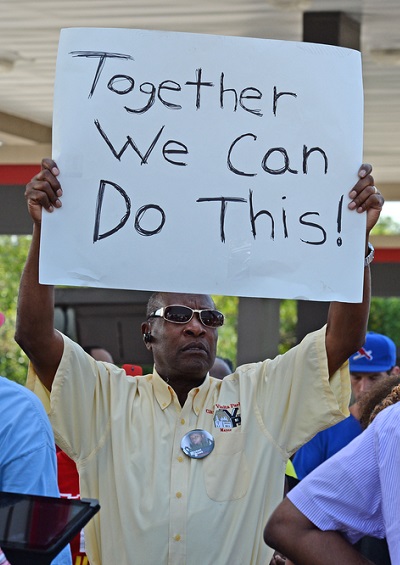

From Ferguson to Baltimore (Via Manassas)

April 28, 2015