Why Moldova Won’t be Russia’s Next Target

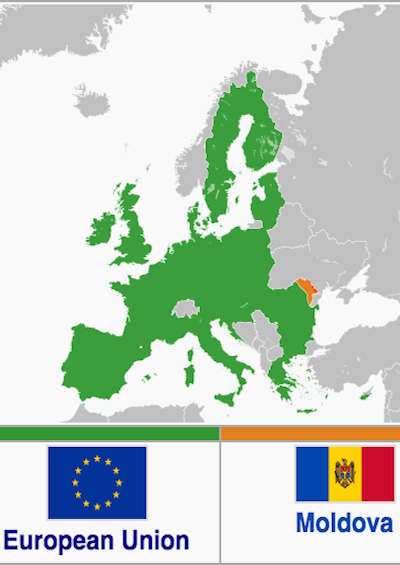

How Russian pressure on Moldova has given the EU a chance to prove itself as an economic partner.

May 22, 2015

On April 9, 2015, Russian military forces conducted a drill in Transnistria, a predominantly Russian ethnic breakaway territory situated in Moldova’s eastern border with Ukraine, which opposes pro-Western initiatives.

The Transnistrian conflict was triggered by the self-proclaimed independence of this Moldovan region in 1990 and frozen in place by the 1992 ceasefire. It remains an unresolved post-Soviet conflict.

The drill may be a scare tactic to end Moldova’s growing closeness with the European Union (EU). But Russia is unlikely to take military action against the country, which ratified its EU Association Agreement in July 2014.

Russia’s meddling continues

The Agreement’s ratification in Moldova was far from unanimous, due to the potential retaliation from Russia. Only 57 MPs out of 101 total voted in favor. There is ample room to try to exploit these divisions by other means.

Instead of invasion, Russia will increase economic pressures on the impoverished Eastern European country. It has already been heftily applying them since Moldova started showing renewed interest in joining the EU.

These measures, however, will probably not prevent closer EU-Moldova ties. In fact, they might grow even closer. Already, Moldova has distanced itself from Russia’s earlier entreaties to join the Eurasian Union — a key test in the EU-versus-Russia quandary facing countries like Moldova.

The Germany effect

Russia’s recent military drill in the autonomous region quickly followed the German Parliament’s ratification of the EU Association Agreement with Moldova, Ukraine and Georgia.

Germany’s seal of approval after years of uncertainty between the European Union and those three countries – due in part to their Russian influence – could accelerate the rate at which other EU countries adopt the agreement.

(For the agreement to come into force, all EU Member States and the EU Parliament have to ratify it. The latter already backed the agreement in November 2014, while Moldova’s neighbor Romania was the first EU country to complete the ratification procedure.)

Why Russia won’t invade

Still, despite the consternation the German vote may have caused Russia’s leaders, and although Russia wants Moldova to end its movement toward the EU, the drill in Transnistria is unlikely to foreshadow war for a number of reasons:

1. After the intervention in Ukraine, sending troops into Moldova would be a sign of weakness in front of the EU’s expansion. It would indicate that Russia feels that its only way of maintaining its influence over the former Soviet Union countries is by invading.

2. In its Ukrainian actions, Russia was trying to send a message to all former Soviet states tempted to enter into new agreements with the EU: Western Europe will not defend its eastern friends against Russia on the battlefield.

While this proved true in the Ukrainian situation, this did not prevent Moldova and Georgia — or Ukraine itself — from seeking to expand their engagement with Europe anyway. There is little point in trying to send that message again after the first one failed.

3. A military intervention in Moldova would never receive the same support from Russian citizens as the one in Ukraine did. This is partly because of the stronger ties between Russia and Ukraine, which is considered an estranged cradle of Russian civilization.

By contrast, Transnistria has already been functionally a Russian outpost since 1992. And – unlike southern Ukraine – the rest of Moldova never had a particularly close or enduring relationship to Russia, even in the 19th century.

It is also partly because of the tremendous economic burden that annexing Crimea currently represents for Russia, which has to invest in the region’s transportation, utility and financial infrastructure, while equalizing its wages and salaries.

So, instead of launching a costly conflict that would likely be unsuccessful, Russia is taking retaliatory economic measures against Moldova. At the end of July 2014, Russia imposed a temporary ban on some vegetables and all fruit imports from the Eastern European country.

The existing ban on Moldovan wines, which represent 10% of all wine drunk in Russia and one of Moldova’s largest exports, was adopted in September 2013 as a pressure tactic to discourage Moldova from signing the EU agreements, even before the Ukraine crisis began.

In October 2014, Russia took an additional step, by imposing a meat ban on all products from Moldova, invoking sanitary violations.

Counterbalancing Russian punishments

These trade restrictions seem to have strengthened the EU-Moldova relationship, as the Union has showed solidarity with Moldova and adopted solutions to counterbalance Russia’s bans.

In December 2014, the European Parliament voted to allow Moldova to export duty-free 40,000 tons of fresh apples, 10,000 tons fresh table grapes and 10,000 fresh plums. The Eastern European country is hoping to extend the trade to meat as well.

Russia also has energy control over Moldova, because of the latter’s dependency on oil supplies. Once again, Europe has shown its support to Moldova, by providing $7 million out of $26 million to build the first pipeline connecting the EU to Moldova, the Iasi-Ungheni pipeline, between Romania and Moldova.

The gas line opened in March 2015 and will provide 1-2% of Romania’s total production capacity. The pipeline’s inauguration allows Moldova to diversify its energy supplies and gain more independence from Russia. The EU has allocated an additional $10 million to extend the line to Chisinau, Moldova’s capital, over the next three years.

The long view

The EU’s measures in response to Russia’s action in both Moldova and the Ukraine have indicated that while the EU may not be willing to respond militarily, it is also not capitulating in front of Russia’s offensive tactics.

Rather, it is counterbalancing Russian actions and proving to be a viable trade and political partner for the Eastern European countries.

Thanks in part to the EU’s encouraging measures, Moldova seems determined to ignore Russia’s increasingly harsh trade measures, become part of the EU and avoid Russia’s Eurasian Union.

With Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia leaning toward the West, the latter project is likely doomed to fail. At the moment, only Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus are currently part of it.

Takeaways

Russia's economic retaliation against #Moldova seems to strengthen Moldova's relationship to the EU.

#Russia's pressure on #Moldova has given the #EU a chance to prove itself as a non-military partner.

#Moldova is safe from invasion after #Russia's #Ukraine interference proved costly and indecisive.